[ad_1]

da-kuk

iShares MSCI India Small Cap Index ETF (BATS:SMIN) is an exchange-traded fund with the mandate of investing in small-cap Indian equities. The fund seeks to track its chosen benchmark index, the MSCI India Small Cap Index. Net assets under management were circa $295 million as of November 2, 2022, according to iShares themselves. That follows net outflows of about $11 million over the past year, at the time of writing in early November 2022. The expense ratio of the fund is unsurprisingly on the higher side at 0.74%; however, this is quite expensive even for country-specific niche funds.

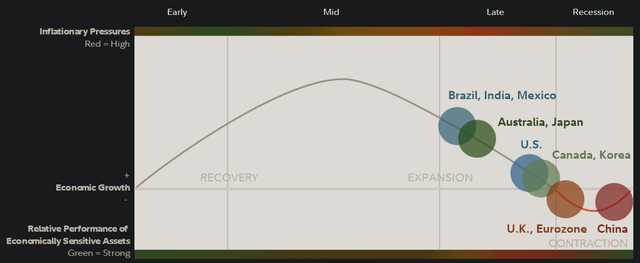

I previously covered SMIN in January 2022 with the expectation that the fund would under-perform vs. the S&P 500 based on valuation alone. However, according to Seeking Alpha data, SMIN has only fallen by -8.43% vs. the S&P 500 U.S. equity index’s fall of -14.61%. India’s positioning in its present business cycle has been lagging behind the United States (see chart below).

Fidelity.com

With equities often leading the economy by about 6-12 months, the recent recessionary pressures that the United States is now facing are more cogent and immediate than the same kind of risks to India, which are more abstract. Fidelity’s chart above is based on economic growth, credit creation, earnings growth, stimulus/policy, and inventory/sales ratios.

Therefore, perhaps the recent under-performance of the U.S. equity market against even the riskier segments of India’s equity market (i.e., small caps) is evidence of this unfavorable U.S. vs. India business cycle positioning.

Going forward, however, we could see an upturn in the ratio between U.S. equities and Indian equities, as eventually India will be heading into a recessionary phase while the U.S. will be already in one with a view to coming out of that dip. We have not yet seen a consensus recession in the United States however, so it is too early to pick the bottom. The ratio between SMIN and SPY, a popular U.S. equity tracker (for the S&P 500) is shown below.

TradingView.com

In fairness, ever since the COVID-19 lows of 2020, SMIN has performed well relative to the United States. Firstly, this was probably due to generally buoyant markets, with higher-beta instruments rallying alongside the S&P 500. SMIN’s five-year beta is about 1.16x as of recent. Then later, as the United States faced the latter stages of its present business cycle, India still found itself in its early stages (as explained above), which would have helped support the appeal for Indian equities internationally.

What is more impressive is that the U.S. dollar has actually strengthened throughout most of this period since the 2020 equity market (short-term) lows. SMIN, being an international equity ETF, has a tendency to move inversely to the U.S. dollar, as non-USD denominated equities are worth less in USD terms as the U.S. dollar appreciates.

SMIN is actually quite well diversified in spite of investing in small caps, with 355 holdings reported at the start of November 2022. My previous concerns regarding valuation were owing to mainly to the fund’s earnings multiple in spite of high local risk-free rates and a likely high total cost of equity. SMIN’s benchmark index referenced earlier offers a forward price/earnings ratio of 21.28x as of September 30, 2022, with a price/book ratio of 3.15x. That implies an underlying forward return on equity of 14.8%, which is fair but not especially high. Meanwhile, Morningstar project a three- to five-year earnings growth average of 19.68%, which is very high, even in light of India’s multi-year range of annual core inflation of circa 4-6%.

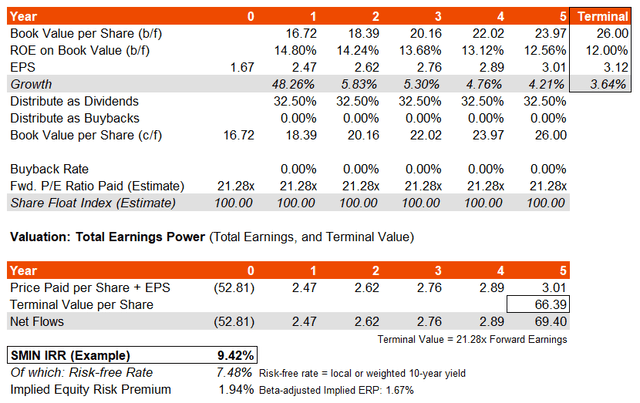

Nevertheless, using the above information, I have constructed a basic model below also referencing the local 10-year yield of 7.48% at present. The total cost of equity should be at least 10-14%, on the low end, using just a simple range of 3.2-5.5% for the equity risk premium multiplied by SMIN’s historical beta of 1.16x, and adding in the local 10-year yield (the “risk-free rate”). The beta here likely understates the country risk premium, but the base cost of equity should be at least in that range of 10-14%. My starting model also holds the forward price/earnings multiple constant.

Author’s Calculations

My model arrives at an implied IRR of about 9.4%, based on total earnings power. In other words, the underlying equity risk premium is tiny.

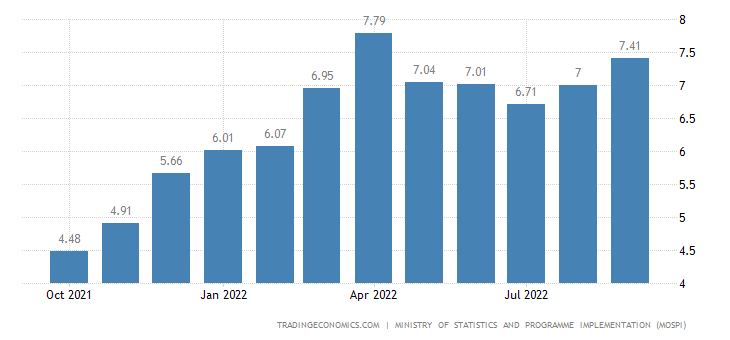

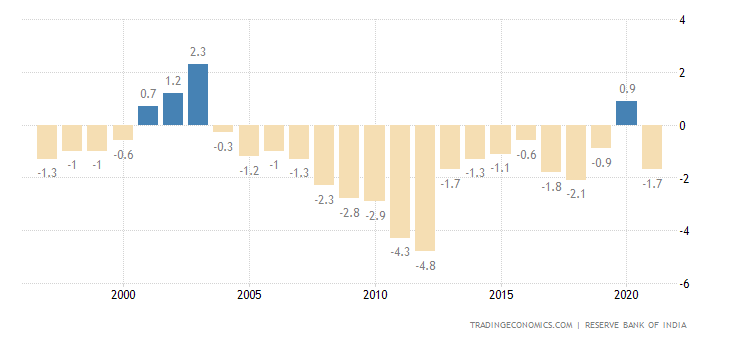

However, we should examine the forward earnings multiple. At the moment it is 21.28x, but is that fair? To begin with, I look at the Indian inflation rate, which is 7.4% at the moment on a headline basis (not core inflation).

TradingEconomics.com

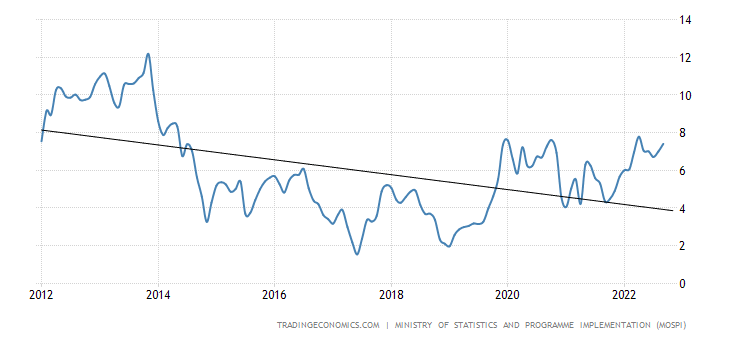

The current 30-year bond yield is 7.62%. If we ignore term premia for the moment, we can use this to get a rough approximation of the “natural rate of interest” (the short-term rate that supports stable growth and inflation). To get there, we could subtract an estimate for long-term inflation of about 4% say, based on past long-term inflation behavior in India:

TradingEconomics.com

However, the term premia mentioned earlier might be as high as 3%. Subtracting 3% from our balance of 3.62% from the figures above takes us to 0.62%. We could assume that the natural rate of interest is about 1% then, which is also what the RBI itself thinks. The most recent RBI (central bank) rate is 5.90%. Subtracting current inflation of 6-7% takes you to a negative rate of as much as -1%, or perhaps 0% (depending on your measure of inflation). So, to cool inflation, the RBI is likely going to need to hike rates by up to 2% more, possibly more than that. This is an environment in which I would not count on a falling risk-free rate to support SMIN’s valuation.

Meanwhile, equity risk premiums are not typically expected to fall too far out of bounds (often 4.2-5.5 in mature markets). Therefore, my indicative valuation that suggests that SMIN is trading with an ERP of sub-2% is evidence of over-valuation.

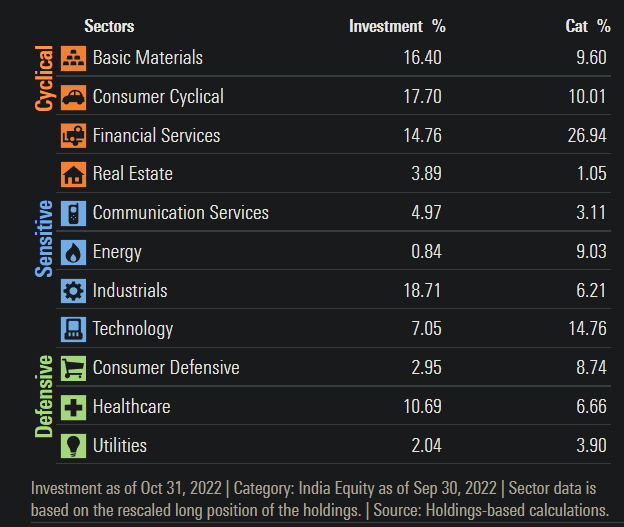

SMIN also invests with a bias toward cyclical and economically sensitive sectors (see below), which are also likely to under-perform once India heads into a contractionary phase.

Morningstar.com

Meanwhile, the Indian rupee is possibly modestly overvalued on the basis that the country maintains a current account deficit.

TradingEconomics.com

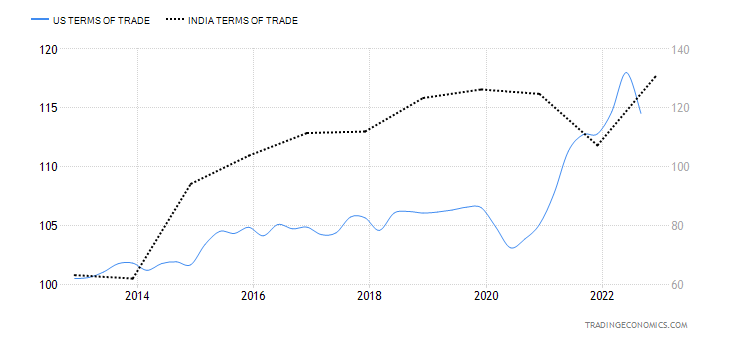

Having said that, the rupee does carry a higher yield than the U.S. dollar, which should support carry trades and therefore rupee demand (both U.S. and Indian rates probably need to rise higher, maybe by similar amounts depending on your expectation of the U.S. terminal rate in this current hiking cycle). Alternatively, based on certain PPP models, the rupee is probably significantly undervalued on a trade basis. Meanwhile, Indian terms of trade are probably going to best the U.S. this year.

TradingEconomics.com

I think the upward trajectory in USD/INR is likely to soften soon, but there is no material “bull case” for the rupee that I can see. A U.S. recession could help, but then again it could drive further safe-haven flows into the U.S. dollar. With a likely still-overvalued SMIN portfolio, coupled with a rupee that isn’t probably going to imminently reverse to strength, I still think SMIN is unattractive, not to mention the longer-term cyclical risk.

[ad_2]

Source links Google News