[ad_1]

chonticha wat/iStock via Getty Images

Investment thesis: The long-term outlook for gold may change dramatically, given fundamental global changes in economics, geopolitics, as well as other factors, such as a deterioration in global logistics. It all makes it more likely for the pure fiat system to be gradually abandoned around the world, in favor of currencies backed by tangible goods or assets. The rising prospects for such an outcome taking root around the world make it imperative for investors to gain some gold exposure.

My own primary preference in this regard is to have some physical gold. However, for shorter-term considerations, such as the recent pullback in gold prices, I like the convenience that the SPDR Gold Trust ETF (NYSEARCA:GLD) has to offer. It allows for more convenient buying & selling of gold exposure, given that it moves in tandem with the gold spot price. The recent pullback in gold prices, therefore in the price of GLD makes this a buying opportunity that investors can exercise with the added convenience of being able to trade gold as they would any stock or exchange-traded fund (“ETF”).

GLD fundamentals and asset safety issues

Before I go on with my analysis of gold’s longer-term fundamentals, based on what we know in regards to the state of the world today, I want to briefly address the basic fundamentals of the GLD ETF.

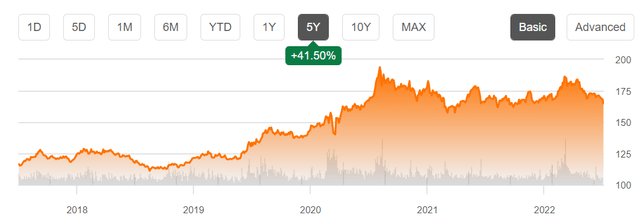

GLD price chart (Seeking Alpha)

Gold spot price (Seeking Alpha)

As we can see, there is not a great deal of discrepancy between the performance of GLD as an asset and the gold spot price. The slight discrepancy is mostly due to the operating expense related to being invested in an ETF.

There have been many discussions in regards to the fact that GLD shares are not the same as owning gold, because one cannot take possession of the physical gold in exchange for the shares. Those objections are noted. As I already pointed out, I am personally more inclined to have physical gold rather than shares in an ETF that holds gold in a vault in order to back GLD shares in circulation. In fact, I prefer gold miners to the ETF, which is why I also have a significant position in Barrick Gold (GOLD), as well as a minor position in Wheaton (WPM) stock, which offers exposure to gold as well as silver. I do, however, see the benefit to buying & selling GLD, for the simple fact that it is very convenient to do so.

Convenience-wise, GLD shares are less than one-tenth in value compared with an ounce of gold, making it more convenient to trade, if one is looking to buy or sell in smaller increments. As I pointed out in a recent article, this year I made a very significant decision in regards to my overall investment strategy, moving from infrequent trading, in other words, long-term buy and hold, with a focus on mostly a small number of stocks, to more incremental moves, where most transactions will involve no more than 1% to 3% of the total value of my investment portfolio. Trading GLD fits that strategy far better than buying or selling entire ounces of physical gold.

There is also the very obvious advantage of buying and selling at the push of a button. It beats carrying bars of gold around to and from the coin and precious metals dealers. There is, of course, also arguably a greater deal of risk involved. For instance, the news may break that for whatever reason, the GLD fund is failing to cover the outstanding share volumes with physical gold held in the vault. It could happen, even though at the moment there doesn’t seem to be any reason to suspect any such mishaps. It is enough of a worry, in my own case, that I prefer to keep GLD as only a relatively small and mostly temporary portion of my overall gold exposure.

The emergence of the tangible asset-backed currencies scenario is becoming more of a reality thanks to the war in Ukraine

Not long ago, it was thought as an inconceivable scenario to see a major country turn away from executing international transactions in any other currency than a handful of mostly developed-world major currencies, with a predominant role played by U.S. dollars as well as euros. Yet this year, we are seeing the emergence of what is arguably the second commodities-backed currency in the world. I say that it is the second such currency because the U.S. dollar is arguably backed indirectly by the Saudi pledge to sell its oil exclusively in U.S. dollars. It is a historic moment for global finance, even though its implications are currently missed, as most of our attention is taken up by the geopolitical events that are giving rise to it.

Russia’s demand to have payments for certain gas & wheat shipments made in rubles creates automatic demand for their currency. It will take time for it to become institutionalized. Assuming that Russia will continue to stick with the policy, it should in theory act as a similar support mechanism that the petrodollar effect has had on demand for the USD within the international financial system, given that there is always something that the fiat money is guaranteed to buy.

If the Russian experiment will be deemed viable and beneficial to its overall economy, there is a good chance that other countries, especially net commodities exporters in the developing world, will follow its example. For instance, Mexico could demand peso payments for its silver exports, which amount to about $2.5 billion every year on average. The external demand that this would create for the peso would, in theory, help to shore up the peso, without having to rely on central bank policies that often have detrimental effects on the economy.

Congo could do the same with its cobalt exports, Chile could do it with copper, and Bolivia with its lithium. There are many developing nations around the world that might see a benefit to replicating Russia’s current experiment in this regard. Then there are countries that do not have the luxury of backing their currencies with commodities exports. The Czech Central Bank is planning a nine-fold increase in its gold reserves, following in the footsteps of its fellow Visegrad group peers Hungary and Poland. It is not yet clear how these countries intend to use their gold reserves, but it is entirely possible that they may bank on strong exports of manufactured goods as a way to earn foreign currency, which can then be exchanged for gold. My guess is that they may be looking to have enough gold on hand in case they, too, might have to back their fiat currencies with something tangible.

There have been other ideas floated around in various parts of the world, including the concept of gold or other precious metals-backed cryptocurrencies that central banks around the world might deploy as a means to secure imports. Perhaps many Central European countries that do not use the euro currency are looking at this possibility. Or perhaps they simply intended to offer gold for certain goods, in case we reach a point where purely fiat currencies will be largely shunned as a method of payment, especially for certain crucial goods. I hope we will not find out too soon how they intend to use that gold, but unfortunately, it does seem that we are increasingly headed in just such a direction.

Perhaps the biggest hit to unbacked fiat currencies acting as mediums of exchange at an international trade level was the freezing of over $300 billion in Russian Central Bank assets that are denominated in USD, euro, and other major currencies that are commonly used in global trade. It amounts to a negation of payment on about $300 billion worth of scarce natural resources that the world bought from Russia and paid in fiat currency. There are probably very few nations around the world that export natural resources that do not also see a significant threat of effectively-being robbed of resources in this manner, by being paid in fiat currencies for exports that they will not be able to use in the future. It is a huge downside to using reserve currency status as a way to arbitrarily deny any nation the use of that accumulated currency.

The Russian precedent is considered to be the beginning of a long process of a loss of confidence around the world in the current global financial system that is dominated by a handful of developed world currencies, mostly centered around the USD and the euro. Another Zoltan (Zoltan Poszar), with far more pedigree in the field of global finance than yours truly, summarized this historical turn in the global financial system in an opinion piece published back in March, which provides contour to the concept of emerging commodity-based money systems. Since then, there seem to be more and more incremental steps that are taken around the world, which seem to confirm that we are headed in this direction, on a slow but steady path.

Investment implications:

I focused most of this article on demand factors, which provides a glimpse into the potential upside for gold prices. The supply factor is what provides a long-term price floor, therefore a certain degree of safety to investors.

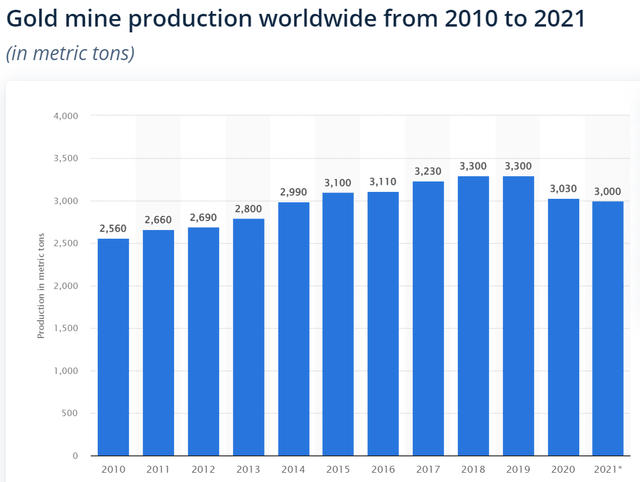

Global gold production by year (Statista)

As we can see, the current mined production of gold declined significantly from the 2018-2019 peak, and it is now sitting at 2014 levels. The main limiting factor that tends to govern global gold supply is the price that miners can sell it for, versus the marginal cost of producing gold. The recent decline in mined supply is a reflection of gold prices in the 2014-2018 period, which led to certain mining investment decisions during that period, based on the prevailing gold price of the period.

Based on this, we can assume that gold prices declining below the $1,500/ounce level will eventually lead to a slowdown in mined production growth or an outright decline in production. This, in turn, leads to a gold price floor that we can currently assume it to be in the $1,500/ounce range. This is, therefore, the long-term downside risk profile of GLD. It could see a long-term decline of about 15% from current price levels, tracing the price of gold, but not much more than that.

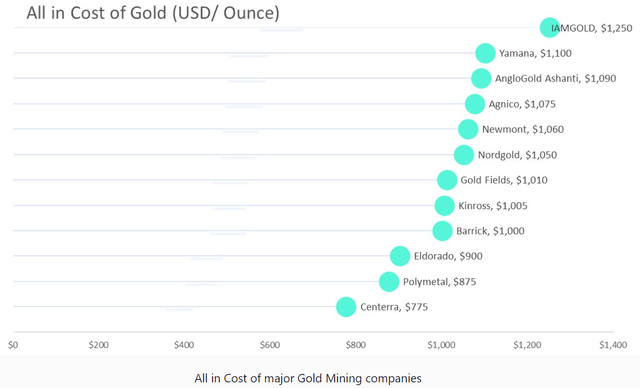

All-in costs of mined gold production for various companies (Money graph it)

The all-in costs of production that many major gold mining companies are reporting may suggest that there may be slightly more downside risk to GLD, based on the assumption that mining companies will choose to invest as long as they can assume that gold prices will be at least at average levels that they need to cover their all-in costs. Generally, these companies want to see a profit, and also a bit of a safety cushion in case of future cost overruns and so on. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that these companies might cut back at least some of their investments if the average price of gold will drop below $1,500/ounce.

Just to clarify, it does not mean that GLD might never decline by more than 15% from current levels. All it means is that it will not see a prolonged period below that price point. A resulting decline in mining investments should help to push the price of gold back up, to at least $1,500. Investors can therefore opt to hang on and limit their losses to perhaps about 15%, on GLD shares purchased at current prices, in a worst-case scenario.

The potential upside for GLD can be virtually unlimited, with growing global economic and geopolitical turbulence making it more likely for gold prices to gain considerably relative to fiat currencies. In real terms, gold prices may not necessarily beat inflation, but at the very least it should act as a wealth-preserving mechanism. In a best-case outcome for gold investors, central banks will create significant demand growth, as they will increasingly feel the need to safeguard their fiat currency systems with tangible assets.

It does look more and more like the post-WW2 global financial system is starting to unravel, or at least shift as an adaptation to new realities this decade. The rise of geopolitical tensions in the process of this shift suggests that the change will not be orderly, but rather destructive, with the resulting magnitude of the damage and speed of the destruction of the current global financial order being amplified. With the fiat system increasingly under pressure, gold will probably see renewed demand as a backing tangible asset, alongside other assets. The recent pullback in gold prices should be seen as a buying opportunity.

[ad_2]

Source links Google News