[ad_1]

Bears are in the driver’s seat

KenCanning/E+ via Getty Images

In my last piece on Seeking Alpha, “Big Tech Has A Lot Farther To Fall”, I explained why I thought large-cap tech stocks are likely entering a “secular” bear market that could see indexes like the Nasdaq 100 (QQQM) fall to the 7000-8000 range and stay there for much of the remainder of the decade.

In this article, I am going to explain why the CARZ ETF is more exposed to a tech reversal than almost any other fund.

First, however, let’s look under the hood.

The First Trust S-Network Future Vehicles & Technology ETF (until recently the First Trust NASDAQ Global Auto Index Fund), according to its prospectus, invests “at least 80% of its net assets in Future Vehicles companies…and Technology companies” In order to be included in the index, “a company must be…engaged in one of the following sectors: (a) electric and autonomous vehicle manufacturing; (b) enabling technologies; or (c) enabling materials”

The index is weighted according to “a float-adjusted market capitalization weighting” formula where “the maximum weight assigned to a single security is 4.5% and the minimum is 0.5%” In other words, big companies are given greater weight than small ones, but that weighting is significantly lower than would be the case in a normal cap-weighted sectoral index like tech sector or discretionary sector ETFs like XLK and XLY where 40% of the holdings are in two companies (Apple and Microsoft in the former, and Tesla and Amazon in the latter). That means that CARZ is exposed to both the benefits and risks of smaller-cap stocks, which will have to be taken into account in our analysis.

What all of this means in practical terms becomes apparent when we look at the fund’s holdings.

|

First Trust S-Network Future Vehicles & Technology ETF Holdings as of 2/11/2022 |

||||

|

Security Name |

Identifier |

Weighting |

Cumulative Weighting |

|

|

Apple Inc. |

AAPL |

4.86% |

4.86% |

1 |

|

Alphabet Inc. (Class A) |

GOOGL |

4.81% |

9.67% |

2 |

|

Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. |

005930.KS |

4.72% |

14.39% |

3 |

|

Toyota Motor Corporation |

7203.JP |

4.58% |

18.97% |

4 |

|

NVIDIA Corporation |

NVDA |

4.47% |

23.44% |

5 |

|

QUALCOMM Incorporated |

QCOM |

4.44% |

27.88% |

6 |

|

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Ltd. (ADR) |

TSM |

4.31% |

32.19% |

7 |

|

Intel Corporation |

INTC |

4.30% |

36.49% |

8 |

|

Tesla, Inc. |

TSLA |

4.14% |

40.63% |

9 |

|

Texas Instruments Incorporated |

TXN |

2.41% |

43.04% |

10 |

|

Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. |

AMD |

2.29% |

45.33% |

11 |

|

Volkswagen AG (Preference Shares) |

VOW3.GY |

2.21% |

47.54% |

12 |

|

Micron Technology, Inc. |

MU |

1.60% |

49.14% |

13 |

|

Analog Devices, Inc. |

ADI |

1.38% |

50.52% |

14 |

|

BYD Company Limited (Class H) |

1211.HK |

1.31% |

51.83% |

15 |

|

Ford Motor Company |

F |

1.17% |

53.00% |

16 |

|

Mercedes-Benz Group AG |

MBG.GY |

1.06% |

54.06% |

17 |

|

General Motors Company |

GM |

1.04% |

55.10% |

18 |

|

Honda Motor Co., Ltd. |

7267.JP |

0.95% |

56.05% |

19 |

|

Baidu, Inc. (ADR) |

BIDU |

0.94% |

56.99% |

20 |

|

US Dollar |

$USD |

0.85% |

57.84% |

21 |

|

Marvell Technology, Inc. |

MRVL |

0.81% |

58.65% |

22 |

|

Volvo AB (Class B) |

VOLVB.SS |

0.79% |

59.44% |

23 |

|

Xilinx, Inc. |

XLNX |

0.76% |

60.20% |

24 |

|

Infineon Technologies AG |

IFX.GY |

0.74% |

60.94% |

25 |

|

Stellantis N.V. |

STLA.IM |

0.74% |

61.68% |

26 |

|

NXP Semiconductors N.V. |

NXPI |

0.73% |

62.41% |

27 |

|

Microvast Holdings, Inc. |

MVST |

0.71% |

63.12% |

28 |

|

Great Wall Motor Company Limited (Class H) |

2333.HK |

0.68% |

63.80% |

29 |

|

DENSO Corporation |

6902.JP |

0.65% |

64.45% |

30 |

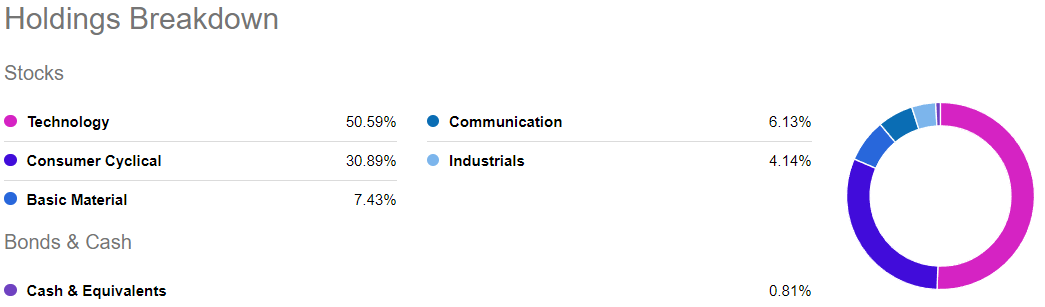

These are the first 30, and there are 70 others after them. It is quickly apparent that this is an auto ETF that is heavily exposed to developments in the general tech space. Effectively, this is consumer tech goods, cars, and semiconductors.

CARZ is more tech index than auto index (Seeking Alpha)

This is not meant as a criticism. In fact, if you are long-term bullish on the future of high-tech auto, this is probably an excellent way to gain exposure to value up and down the chain, without having to predict precisely where the next breakthrough will occur. But, this also makes the fund vulnerable to the sort of macro-reversal I have been anticipating in this space for a year now and which is now beginning to percolate.

Now, I have already described my general case against big tech in “A Primer On Long-Term Sector Rotations And Where We Are Now” and I updated and augmented that with an analysis of the history of tech valuations in my last piece, referenced at the beginning of this article.

At the risk of oversimplification, these pieces argue that we are at the late stages of a secular tech boom/energy crash, and that in previous instances (particularly the 1920s and 1990s), this has been followed by a vicious long-term reversal in tech stocks both on a relative and absolute basis. Even in the inflationary 1970s, in real terms, tech returns were negative (using data from Fama-French’s value-weighted Business Equipment index), and at some points sharply negative (-50% in nominal terms from the conclusion of the tech boom in 1969 until after the 1973 oil shock).

Tech has always behaved as a kind of alter ego to the energy sector. Not only do they tend to move in opposite directions in relative terms but they both have this tendency of alternating between ‘inevitabilities’, so to speak. In the same way that energy and gold and the commodity space generally seemed unstoppable and inevitable in the 2000s, tech seems inevitable now. Then, for reasons that only appear obvious later (Enron! the housing market!), the bottom falls out.

One objection to my bearish tech thesis that comes up and that is echoed among the present cast of ‘tech inevitablists’, of which Cathie Wood may only be the most visible, is of the inevitability of progress, and especially technological progress. Not only will technology currently available become more widely adopted but that technological progress increases exponentially. There is now a virtuous cycle of technological development moving at such a rapid pace that soon it will be able to finance everybody’s UBIs. (UBIs may be coming but they are unlikely to be financed by big tech).

That is a line of argument that cannot be disproven. My counter rather is that these forces do not necessarily translate into stock returns. The 1930s are probably the best example. The technological progress that occurred in the three decades prior to the crash of 1929 dwarfed what has been happening in the last 30 years. I have described this indirectly in “How The Fed Is Knocking The World Off Balance” The transformation reached into every aspect of life: urbanism, suburbanism, labor, transportation, media, politics, fashion, industrialization, art, even human posture(!). If you look at images of daily life prior to the 1900s and then at images of life in the 1920s, the former appear foreign while the latter are almost immediately relatable. This was a global civilizational makeover.

Robert Gordon describes the 40-year period from 1890 to 1930 as “an era of improvement without comparison in human history.” And, it did not stop in the 1930s. I am going to quote extensively from the end of Chapter 16 of Gordon’s excellent The Rise and Fall of American Growth to drive home this point.

“For every 100 units of electricity that were added to the productive process during 1902-1929, another 230 units were added between 1929 and 1950.”

The “focus on the 1920s as the breakthrough decade misses that the full force of electricity expansion in manufacturing and the rest of the economy took place between 1929 and 1950.”

“The trauma of the Great Depression did not slow down the American invention machine. If anything the pace of innovation picked up in the last half of the 1930s. This is clear in the data assembled by Alexopoulos and Cohen on technical books published. The dominance of the 1930s…is supported by Kleinknecht’s count of inventions by decade.”

“By 1940, automobile manufacturers had achieved the dream of producing automobiles that could go as quickly as the highways would allow them…”

“[F]rom the discovery of the east Texas oil field to the development of many types of plastics now considered commonplace, the 1930s added to its luster as a decade of technological advance.”

“[T]he Great Inventions of the late nineteenth century, especially electricity and the internal combustion engine, continued to alter production methods beyond recognition not just in the 1920s but in the 1930s and 1940s as well. Alex Field revitalized US economic history by his startling claim that the 1930s were ‘the most progressive decade’.”

You can go through many of the charts he included on technological adoption rates, expansions of the highway, education rates, and so on which support these declarations.

The point is not, as some argue, that fundamentals don’t matter. It’s just that they don’t matter the way we think they should matter. My argument, in line, I believe, with Schumpeter’s theory on the relationship between markets and technological transformations, is that technological supercycles are expressed primarily through commodity prices, inflation rates, and yields, especially the earnings yield.

And, the earnings yield has two components: prices and earnings. In the 1920s, yields were depressed because of high stock prices; in the 1930s, they were depressed because of low profits. And tech stocks, using real returns of the large-cap Fama-French 12-sector indices, were one of the worst-performing sectors of the 1930s.

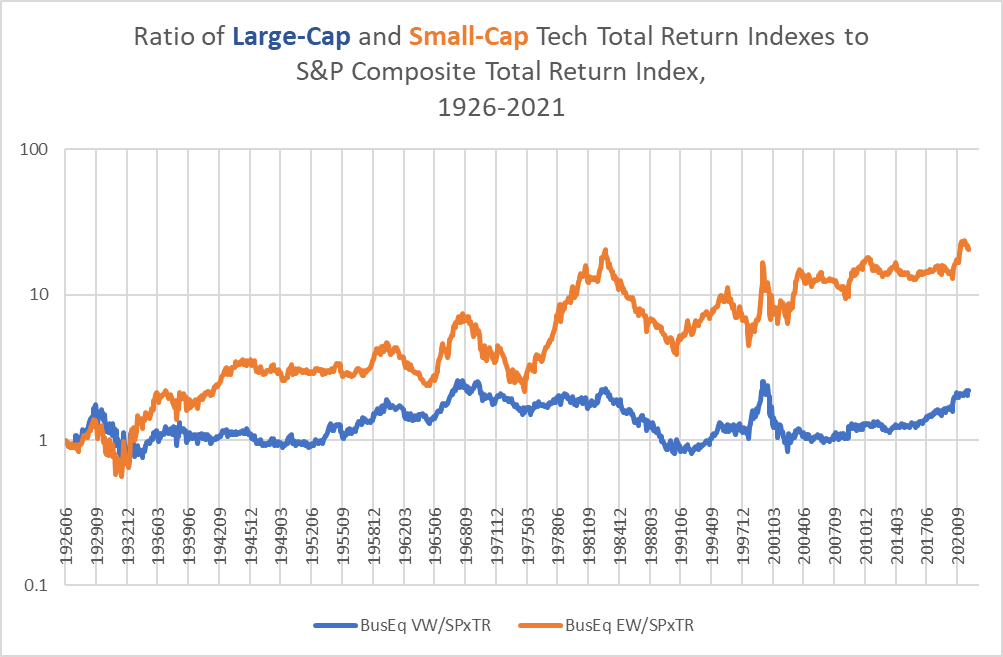

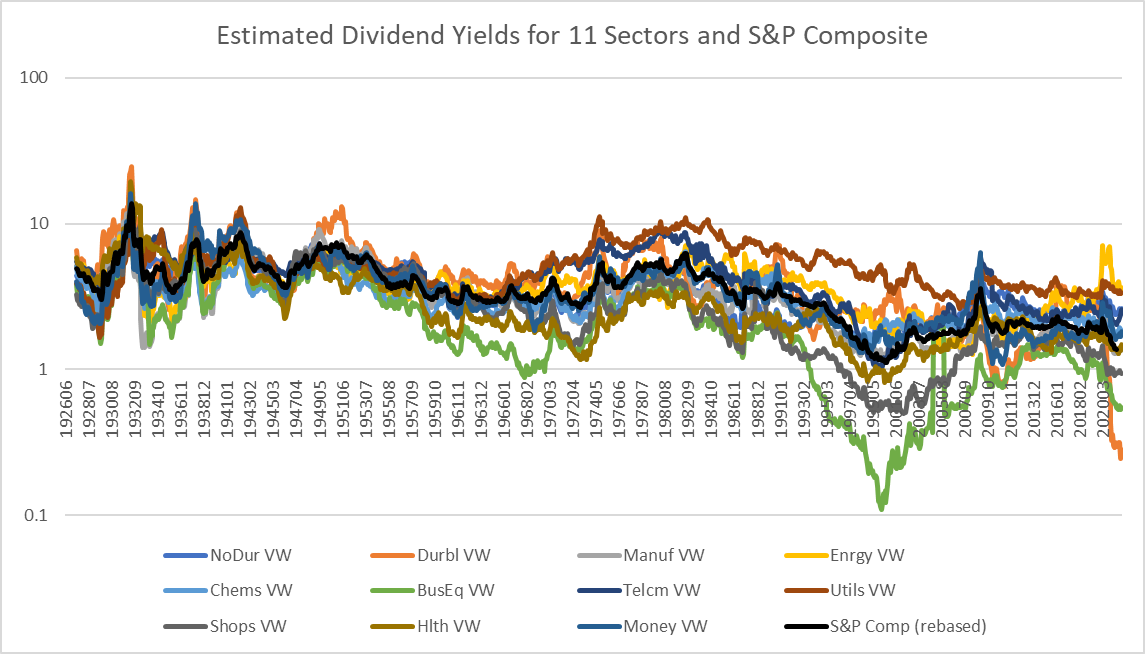

Chart A. Tech stocks have always underperformed in equity bear markets (Own calculations from Fama-French data)

In the great bear markets of the 1930s, 1970s, and 2000s, losses were always amplified in large-cap tech stocks. Small-cap tech stocks did better, particularly after an initial period of severe underperformance (as in the 1929-1932, 1968-1974, and 2000-2002 markets).

This is one of the mixed blessings of an index like CARZ. The exposure to smaller-cap tech stocks could pay off on a relative basis in the (very) long run, if one is willing to endure perhaps years’ worth of inferior poor relative returns and risk severe absolute losses.

But, to return briefly to the point about the relationship between technological progress and stock returns. Technology booms filter through markets in their own particular way. They have almost always occurred before ‘secular’ bear markets, especially when energy markets were soft during the preceding tech boom.

Another way of putting this is that technological booms are not confined to the tech sector, and they have nonlinear effects. One infamous example is the inflationary impact that technological progress has on services, despite the deflationary impact it has on goods.

I certainly could be wrong, but my reading of market history as spelled out in previous articles is that large-cap tech stocks will be a drag on markets collectively and on tech-heavy indexes like CARZ. But, what about the auto and small-cap components?

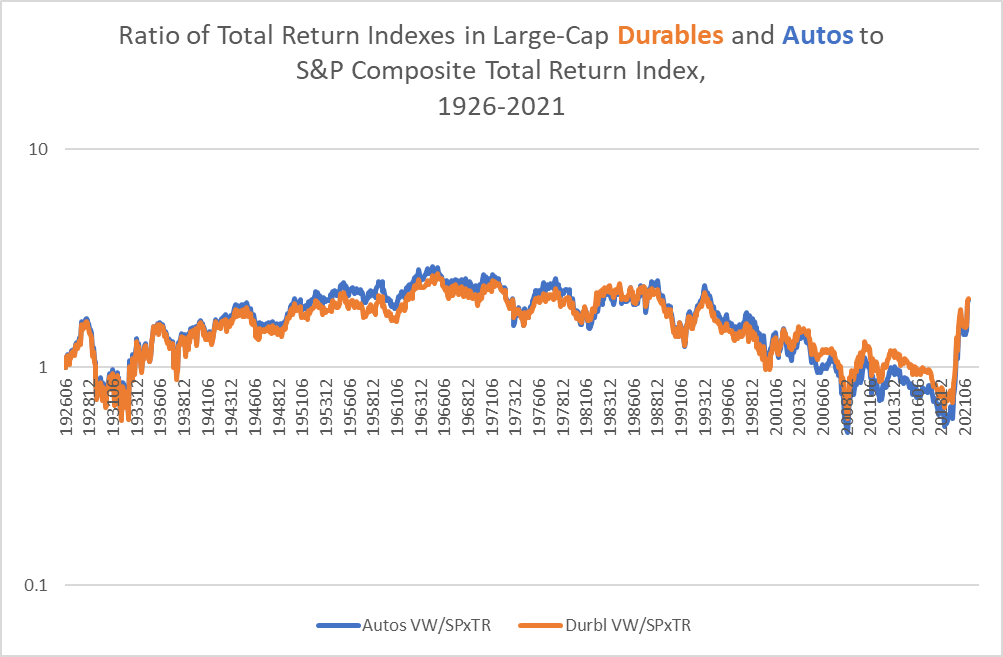

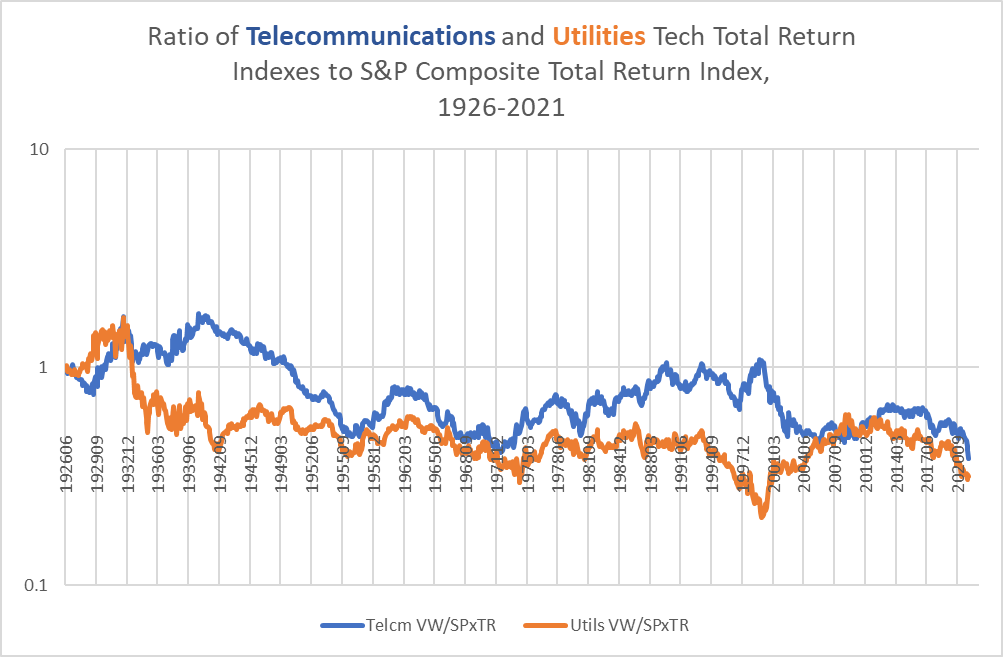

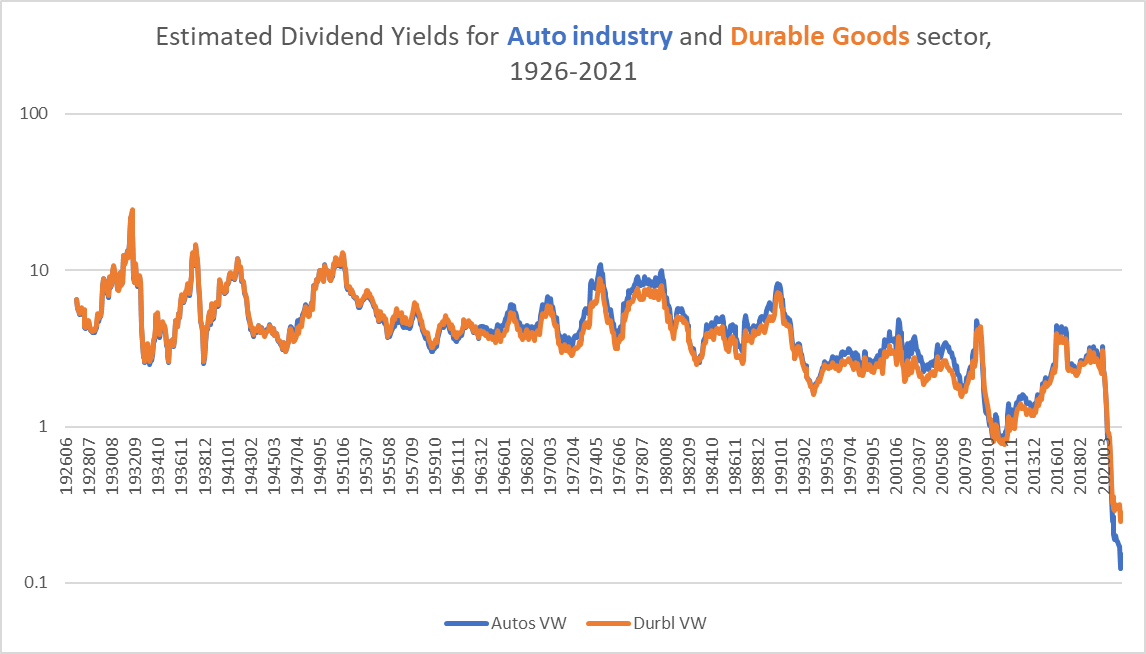

In my previous article, I briefly noted that in previous tech booms, there was frequently another sector that appeared to go along for the ride. In the 1920s, it appeared to be utilities. In the 1990s, telecommunications. And this go-around, it appears to be durable goods stocks, which, as can be seen in the following chart, has been dominated by the auto industry.

Chart B. Imagine a bad pun about cars breaking the speed limit (Own calculations from Fama-French data)

It appears, actually, that the auto sector was also involved in the tech boom of the late 1920s but ducked out first. The utilities boom may have been anticipation of the coming crash.

Chart C. Other sectors participated in previous tech booms in 1920s and 1990s (Own calculations from Fama-French data)

In other words, this may be our second dual auto/tech boom.

And, it is no secret from whence this boom has arisen.

Chart D. Tesla has outperformed traditional auto makers… (StockCharts.com)

Chart E. …even as traditional automakers rally against the market (StockCharts.com)

Old manufacturers have had a nice cyclical boom that has not really made an impression on the longer-term relative performance. It is Tesla that has forged the way ahead for the sector.

The auto sector is, in other words, not quite itself. It has been infected by the tech bug and is vulnerable to the same processes that we just described at operation in the traditional tech space.

This is apparent in valuations as well. In the following chart, I estimate dividend yields based on the contrast between total returns and price returns.

Chart F. Sky-high valuations in tech and consumer discretionary stocks push dividend yields to record lows (Own calculations from Fama-French data)

The durable goods sector has achieved exceeded only by the tech sector’s dot.com boom. Even if we make allowance for the fall in dividend payout ratios across stock markets since World War II, these are extremely high.

In fact, dividend yields in the auto sector appear to be inches away from the levels seen in tech two decades ago.

Chart G. Dividend yields tell us just how out of control the market is (Own calculations from Fama-French)

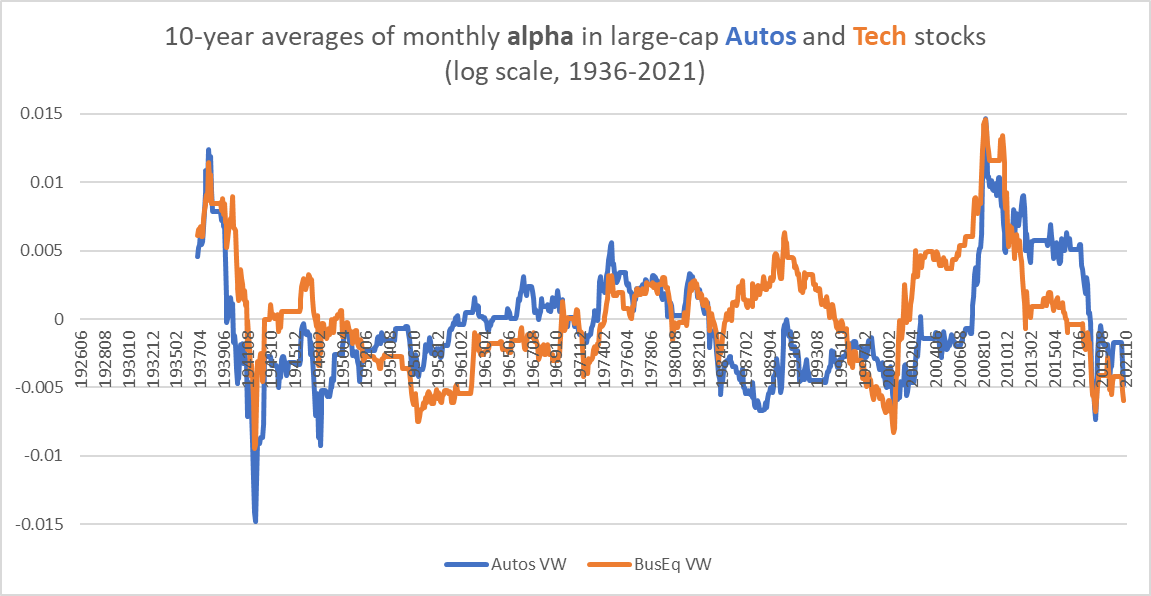

Large-cap auto industry and the business equipment sector stocks have had fairly firm correlations with both subsequent 7.5-year returns (0.35 and 0.42, respectively) and negative correlations with subsequent dividend growth (-0.23 and -0.45), suggesting that both are more likely to see growth than total returns. The correlation between business equipment’s long-term historical dividend growth and price returns is -0.06 since 1926 and -0.26 since 1947. There is a slight tendency, therefore, for high dividend growth to translate into lower returns in tech stocks. On a relative basis, dividends in long-duration growth stocks may hold up well, but that does not necessarily imply positive relative returns.

If we turn to small caps, auto industry dividend yields are strongly correlated with total returns (0.55) but negatively correlated with dividend growth (-0.09). Business equipment small caps have a modestly negative correlation with subsequent dividend growth (-0.34) that translates into a total return correlation of 0.24 that makes up for the weak correlation with price returns (0.04).

Again, history suggests that these extremely high valuations may result in more cash available but without translating either into price returns or total returns. Chart B suggests that there may be opportunities to buy small-cap tech stocks in a bear market, but it is best to wait until after they crash.

This is what happened in 2003 with Microsoft, well after the dot.com peak. Returns remained flat relative to the peak while the company started forking cash over to investors.

Perhaps the final question is whether or not now is the time to abandon this combination of auto and tech. If the dividend yield on the auto sector is something like 0.1%, who is to say that it cannot go to 0.05%? If we have learned anything over the last decade, it is that there is apparently no absolute upper bound to valuation ratios nor lower bounds to interest rates. If markets wanted to send these stocks to double their current levels, there is no theoretical reason why this should be impossible.

I suspect, however, that the current inflation-shock will put a check on things.

I did a cross-correlation of World Bank commodity inflation with both stock market performance (across the Fama-French 49 industries and 12 sectors small and big) and subsequent earnings growth in the S&P 500. The most powerful predictor of negative short-term returns (approximately a year) and growth shocks was the fertilizer price index. The second-most vulnerable industry was small-cap auto stocks (-0.51) and the most vulnerable sector was small-cap durable goods (-0.52). Large-cap auto stocks were only a little farther behind (-0.46).

Currently, we are in our third-most severe bout of fertilizer inflation in the last sixty years. The previous two, in the early 1970s and 2008, coincided with oil shocks, but oil prices have a weaker (negative) correlation with stock performance across all sectors and industries.

It is not obvious how fertilizer inflation would translate into auto industry weakness, but one suspects that the path is through the consumer, that as price pressure is passed through to potential buyers on the level of staples, they delay their purchase of discretionary items, especially big-ticket items like cars. In an inflationary environment, this may benefit electric vehicles, which would be relatively well placed to ignore higher fuel charges, but once consumers settle in for a battle with inflation, it is likely cars will be an early casualty.

Finally, as I mentioned in my previous article, I have been working on an algorithm that provides periodic buy and sell signals in stocks, and I have backtested them against all of the Fama-French 49 industries and 12 sectors in both big and small-cap stocks, as well as the S&P Composite and across value and growth. This algorithm seems to generate long-term alpha in about two-thirds of these indices. Among them are auto and tech stocks.

Chart H. Backtests of stock algorithm (Own calculations from Fama-French data)

Currently, the CARZ index has been stalled at roughly the same levels for over a year. The algorithm has dipped out of buy and sell territory for much of that time.

Chart I. Keep an eye on this index (StockCharts.com)

At present, the algorithm says it is a buy, but because of the long-term pressure that tech-heavy indices are likely to come under over the next decade, as well as the current inflationary pressure, I believe that the index has effectively peaked. Safer indices like utilities (XLU) or staples (XLP) would likely provide better protection for the time being. Right now, I think that those who remain interested in the tech-auto play, a breakout to either side of the $57-$65 range would provide a signal as to the indexes short-term tendencies. But, over the next two years and out until the end of the decade, I am bearish.

[ad_2]

Source links Google News