[ad_1]

Coming out of a seven-year hibernation.

Byrdyak/iStock via Getty Images

The Consumer Discretionary Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLY) is currently one of the worst performing sectors of the S&P 500 sectors. In this article, I am going to argue that this is likely only the beginning. Of the S&P 500 sectors, the tech-rich sectors like XLY, Communication Services (XLC), and Information Technology (XLK) are most likely to see negative returns over the coming decade, and this bear market-a bear market in both absolute and relative terms-has likely already begun. Moreover, there is considerable risk of sharply negative returns over the next one to three years, especially in XLY.

Before getting into the nitty-gritty details, let me briefly explain why.

The macro context is bad for tech stocks

One way to break down this argument is to separate it into long-term and short-term cases. The long-term case is that the market is “due” for a major reversal in long-term sector performances. When tech stocks thrash cyclicals (especially energy) over seven-year durations as thoroughly as they have over the last seven years, the next seven years have typically seen a near-complete reversal in sectoral fortunes. Thus, we are likely to see energy outperform tech through the remainder of the decade.

We can layer on top of that tech’s role in the broader market. Tech booms have typically occurred at the conclusion of “secular” bull markets generally (for example the 1990s). What follows, by definition, is a “secular” bear market for the market as a whole (as with the 2000s).

If we combine these two principles-that long-term outperformance by tech (or any sector, really) is typically followed by long-term underperformance and that tech booms occur in the final stages of a bull market-we arrive at the conclusion that tech stocks are likely to underperform long-term relative to a market that will experience little to no returns. This is why the Nasdaq swung between 25-50% of its 2000 peak level over the subsequent decade, even though there was enough inflationary pressure to keep the S&P 500 flattish and to boost commodities to levels that had not been seen since 1980.

Not only do tech booms tend to occur at the conclusion of “secular” bull markets in stocks, but the market as a whole tends to see a combination of both extreme PE levels and above-trend levels of earnings growth. Over the last century, each time this has occurred (the 1920s, the 1960s, the 1990s, and 2010s), markets have experienced 7-14 years of flat to negative returns (as in the 1930s, 1970s, 2000s and 2020s(?)). Tech underperformed in each of these long-term bear markets, and interestingly, it did not particularly matter if the bear market was inflationary (as with the 1970s and 2000s) or deflationary (1930s).

This is the fusion of two arguments I have been making over the last year and which can be found in greater detail in The Death Of Irrational Exuberance, where I present S&P 500 price and earnings estimates for the remainder of the 2020s that seem to best fit the historical patterns discussed above, and Big Tech Has A Lot Farther To Fall, where I updated my thesis for long-term sector rotations.

Now, the short-term case, which ties in to the long-term one: “secular” bear markets in stocks are cyclical markets. This is a point I tried to make very simply in Being A Bear Is More Complicated Than It Looks. This axiom can be interpreted in two ways. First, bear markets typically experience a handful of wild cyclical swings along the way, and again, it does not matter whether markets are inflationary or deflationary. Think back to the 2000s. We saw two epic crashes, one at the beginning of the decade and one at the end. Similar things happened in the 1970s and the 1930s.

The other way to interpret this is that cyclicals outperform in bear markets. Energy, for example, not only outperformed most other sectors in the inflationary bear markets of the 1970s and 2000s but also the deflationary 1930s.

Finally, the relative resurgence of cyclicals during bear markets typically occurs before the (usually) tech-led bull market ends. Thus, in the final two years of a “secular” stock boom, we will see a surge in commodity prices and interest rates, often off of some crisis low. In 1997-1998, for example, there were a series of emerging markets crises that threatened global equity and commodity markets. Once this stabilized, both tech stocks and commodity prices shot higher until the dot.com crash that began in 2000 morphed into a cyclical downturn that lasted until about 2003. Energy markets seem to be the key. I have described this interaction in multiple articles, but as it pertains to the role of energy, A Primer On Long-Term Sector Rotations And Where We Are Now probably deals with this in greater detail.

That is the macro backdrop (as I see it). But, what does this mean for the XLY specifically? After all, the consumer discretionary sector is not typically known for being necessarily high tech. In fact, most of the XLY is retail.

My bear case for XLY in a nutshell

The XLY is a somewhat odd combination of the service sector (mostly retail) and consumer durables (mostly the auto industry). But, one thing these two elements have in common is that they have both been “infected” with the technology bug over the last decade. For the reasons outlined above, that was great on the way up but will likely prove to be quite bad on the way down.

On top of that, these two industries both have unsustainably high valuations relative to their historical levels. That is typically followed by long-term bear markets. We will look at that in a moment.

For the short term, both of these industries are more vulnerable than average to commodity shocks, which may explain the timing and speed of the downturn in XLY relative to many of the other sectors.

But, before we look at historical metrics, let’s look inside the sector.

Breaking down the XLY

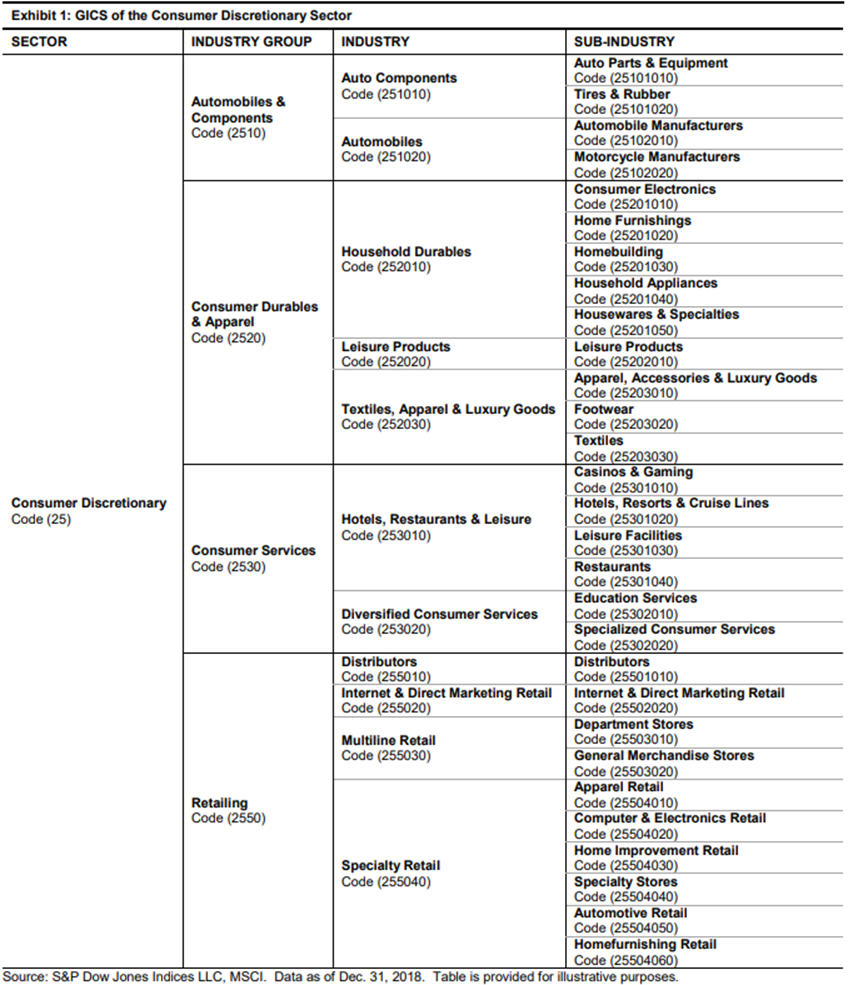

The XLY is comprised of S&P 500 stocks classified by GICS criteria into a pyramid of sectors, industry groups, industries, and subindustries that are each grouped together by certain clusters of financial correlations. The following table from SPGlobal.com shows the great variety of businesses included in the consumer discretionary sector.

Table 1. The Consumer Discretionary sector is comprised of four industry groups. (SPGlobal.com)

For the sake of simplicity, we are going to stick with the four industry groups: Automobiles & Components, Consumer Durables & Apparel, Consumer Services, and Retailing.

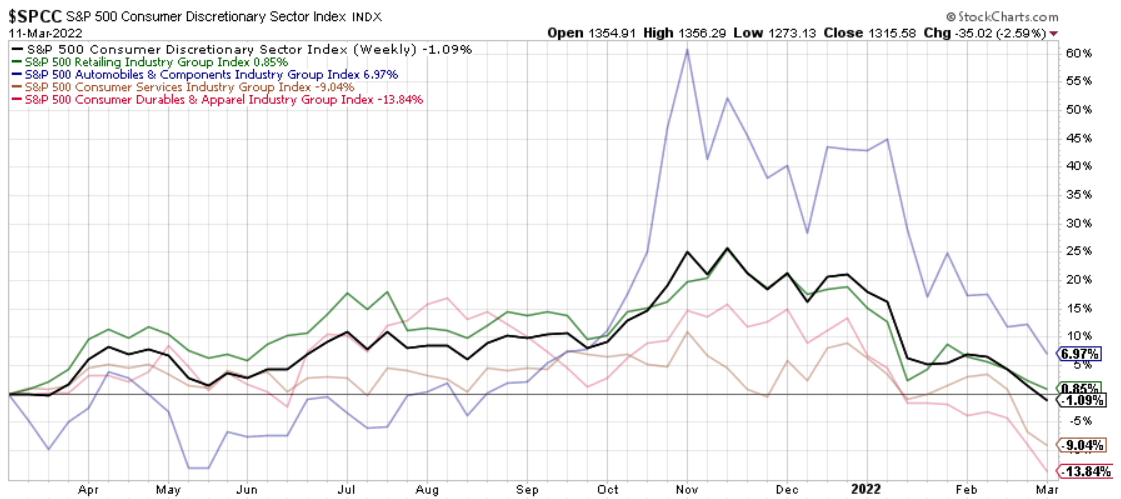

The following chart from Stockcharts.com shows the price performance of the consumer discretionary sector alongside those of the four constituent industry groups.

Chart A. XLY’s industry groups are near 52-week lows. (Stockcharts.com)

From this perspective, performance has been driven primarily by the Retailing Industry Group, which makes up about 50% of the sector by market-cap. Each of these indexes are near 52-week lows except for Automobiles & Components, which has been trying to close the gap.

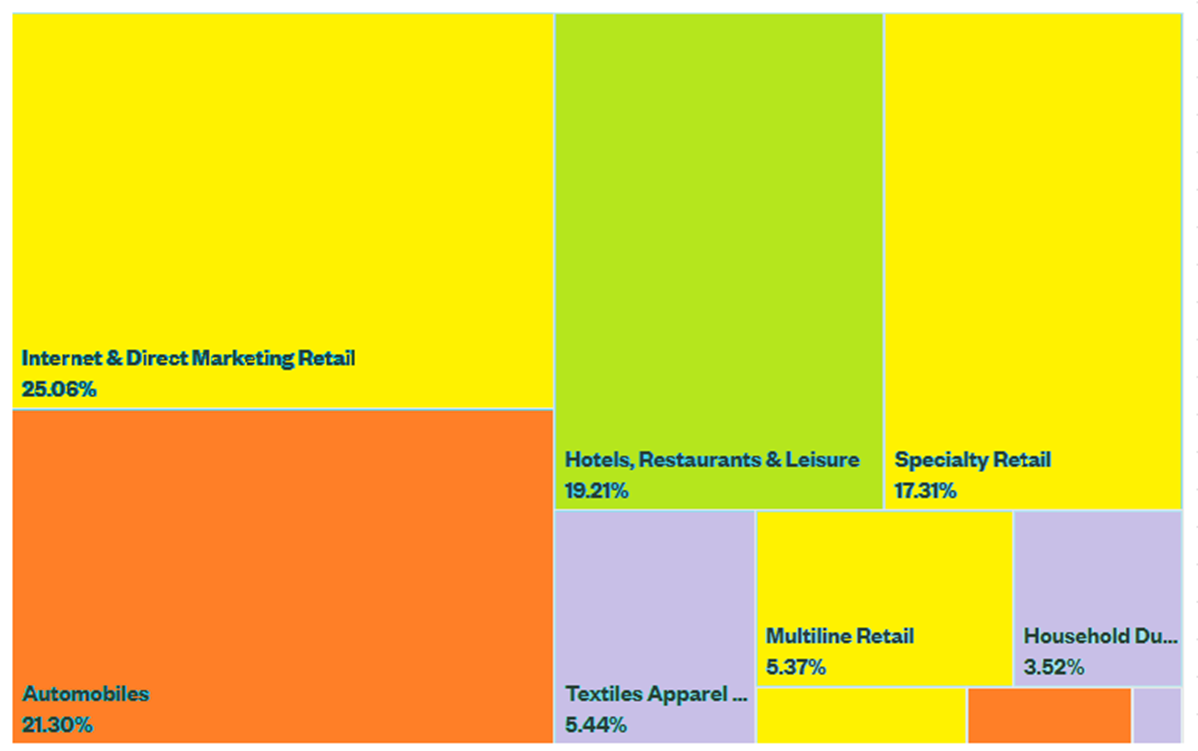

The following chart, from State Street Global Advisors, shows industry weightings, which I then colored according to industry group, with Retailing in yellow, Autos & Components in orange, Consumer Services in green, and Consumer Durables & Apparel in purple.

Chart B. Retail makes up half of XLY. (State Street Global Advisors)

In order to analyze XLY on a historical basis, we need to classify the ETF’s holdings according to SIC values and then assign them to Fama-French industries and sectors. Since Fama-French data goes back to 1926, we can then look at how these types of stocks have behaved under various market regimes.

The following table lists the top 20 holdings of the XLY, their respective GICS-assigned industries and the Fama-French 12-sector classification.

Name |

Ticker |

Weight |

Cumulative |

GICS Industry |

FF12(own calculations) |

|

|

Amazon.com Inc. |

AMZN |

23.6 |

23.6 |

1 |

Internet & Direct Marketing Retail |

Shops |

|

Tesla Inc |

TSLA |

17.7 |

41.3 |

2 |

Automobiles |

Durables |

|

McDonald’s Corporation |

MCD |

4.8 |

46.1 |

3 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Shops |

|

Lowe’s Companies Inc. |

LOW |

4.5 |

50.5 |

4 |

Specialty Retail |

Shops |

|

NIKE Inc. Class B |

NKE |

4.2 |

54.7 |

5 |

Textiles Apparel & Luxury Goods |

Manufacturing |

|

Home Depot Inc. |

HD |

4.1 |

58.8 |

6 |

Specialty Retail |

Shops |

|

Target Corporation |

TGT |

3.0 |

61.9 |

7 |

Multiline Retail |

Shops |

|

Starbucks Corporation |

SBUX |

3.0 |

64.8 |

8 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Shops |

|

Booking Holdings Inc. |

BKNG |

2.4 |

67.2 |

9 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Other |

|

TJX Companies Inc |

TJX |

2.1 |

69.4 |

10 |

Specialty Retail |

Shops |

|

Ford Motor Company |

F |

1.8 |

71.2 |

11 |

Automobiles |

Durables |

|

General Motors Company |

GM |

1.8 |

73.0 |

12 |

Automobiles |

Durables |

|

Dollar General Corporation |

DG |

1.4 |

74.4 |

13 |

Multiline Retail |

Shops |

|

O’Reilly Automotive Inc. |

ORLY |

1.3 |

75.7 |

14 |

Specialty Retail |

Shops |

|

Marriott International Inc. Class A |

MAR |

1.3 |

76.9 |

15 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Other |

|

Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. |

CMG |

1.2 |

78.1 |

16 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Shops |

|

Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc |

HLT |

1.1 |

79.3 |

17 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Other |

|

AutoZone Inc. |

AZO |

1.1 |

80.4 |

18 |

Specialty Retail |

Shops |

|

Yum! Brands Inc. |

YUM |

1.0 |

81.4 |

19 |

Hotels, Restaurants & Leisure |

Shops |

|

Dollar Tree Inc. |

DLTR |

1.0 |

82.4 |

20 |

Multiline Retail |

Shops |

By my count, 58% of the index is classified as Shops (including restaurants), 23% Durables (22% Autos), 12% Other (mostly hotels, transportation, and construction), and the rest Manufacturing, Nondurables, and Business Equipment. In short, 80% of the index is made up of Shops (retail and restaurants) and Autos, so I am going to focus on those two groups.

And, because I have already presented my analysis of the auto industry in CARZ Is Out of Gas, I am going to outsource the analysis for the auto industry to that article, but I will briefly summarize it here.

Are Teslas cars, or are cars no longer cars?

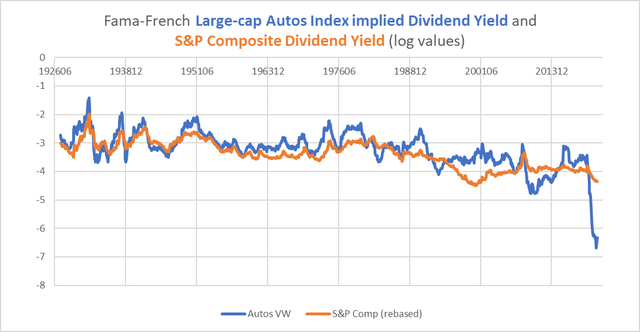

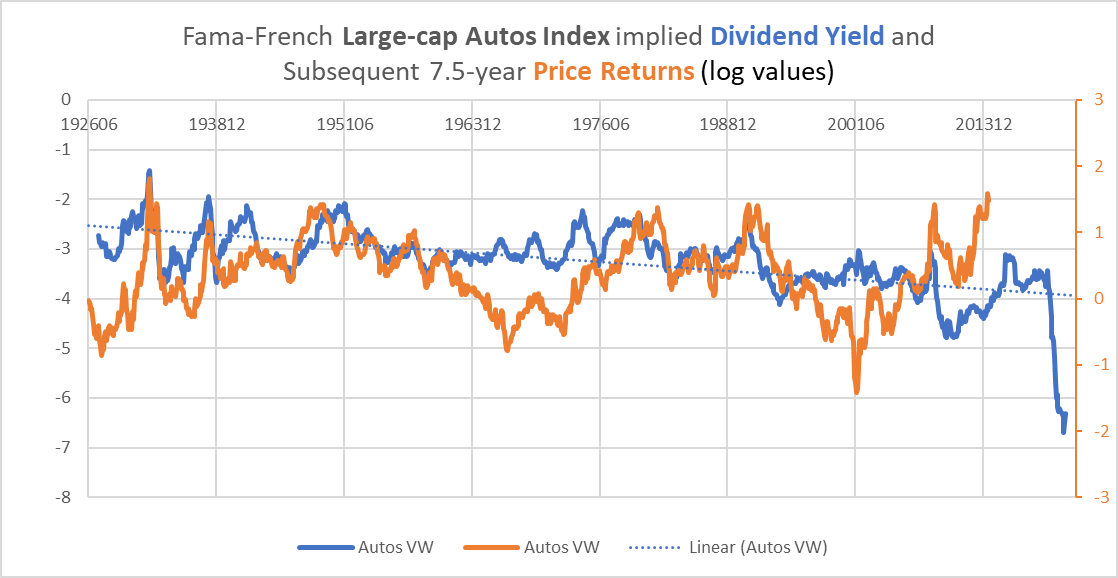

Using the dividend yield as a proxy for historical valuations, it is clear something has changed in the auto sector.

Chart C. Dividend yields on Auto stocks have been shockingly low. (Fama-French, Shiller)

Historically, the dividend yield has been only a mediocre predictor of auto stock returns.

Chart D. Auto industry dividend yield only modestly correlated with subsequent returns. (Fama-French)

But, if Autos stocks are behaving like tech, then that might change things. As we saw with the Software index in our treatment of XLC, tech valuations tend to be quite predictive of future returns.

In other words, if Autos are to be treated by tech standards, chances are they are going to see a severe long-term correction. If they are going to start being treated like cars again-and virtually all of the Autos performance is coming from Tesla, which constitutes about 80% of the XLY’s auto holdings-then they will probably no longer trade at tech-like premiums.

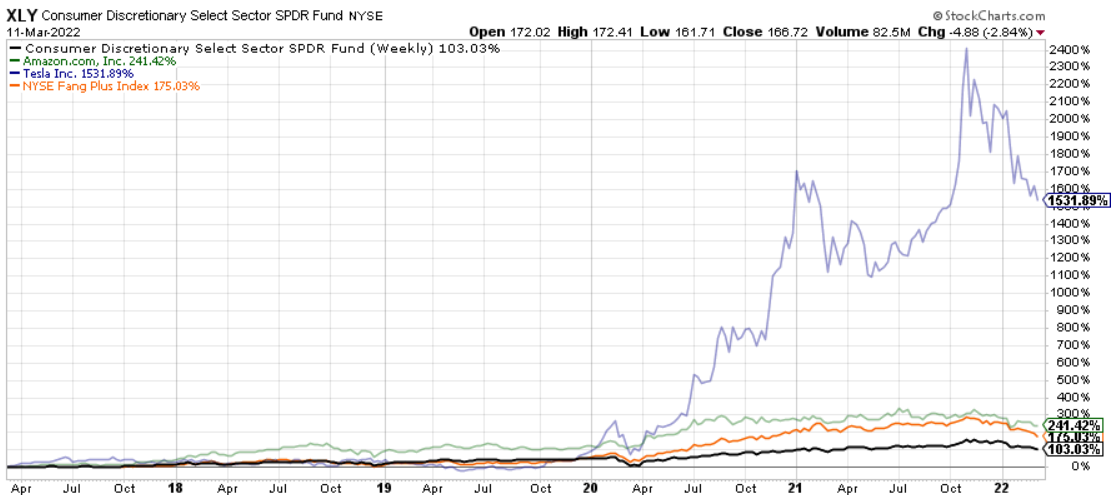

Chart E. Tesla and Amazon have been trading with tech-like results. (Stockcharts.com)

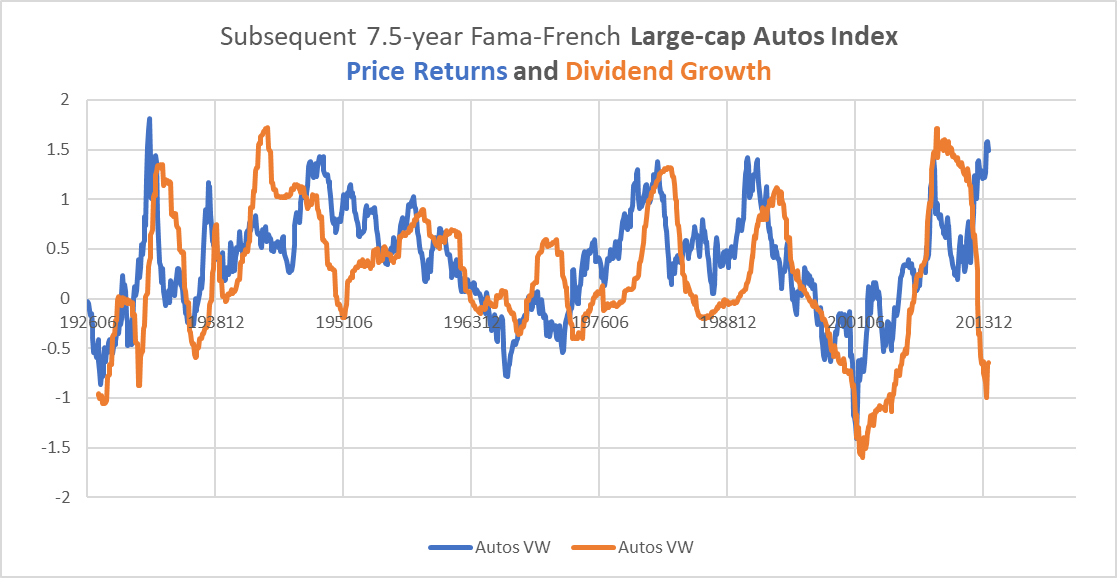

Historically, auto stocks effectively traded with their rate of dividend growth (with a bit of a lag built in).

Chart F. Up until recently, auto industry prices and dividends moved together. (Fama-French)

But Tesla has disrupted that relationship, which is partly why the dividend yield has fallen to such extreme lows, and the company has no plans to start paying dividends any time soon. Again, as we saw with Software industry stocks in the XLC article linked above, in tech stocks, low dividend yields tend to be followed by low returns and high dividend growth. What pattern holds going forward depends, it seems, on whether or not Tesla is to be traded as a car company or a tech company, but neither is especially promising for stock performance for the remainder of the decade. To put this more roundly, Tesla’s best hope for the next decade is to find a way to be traded as a commodity producer.

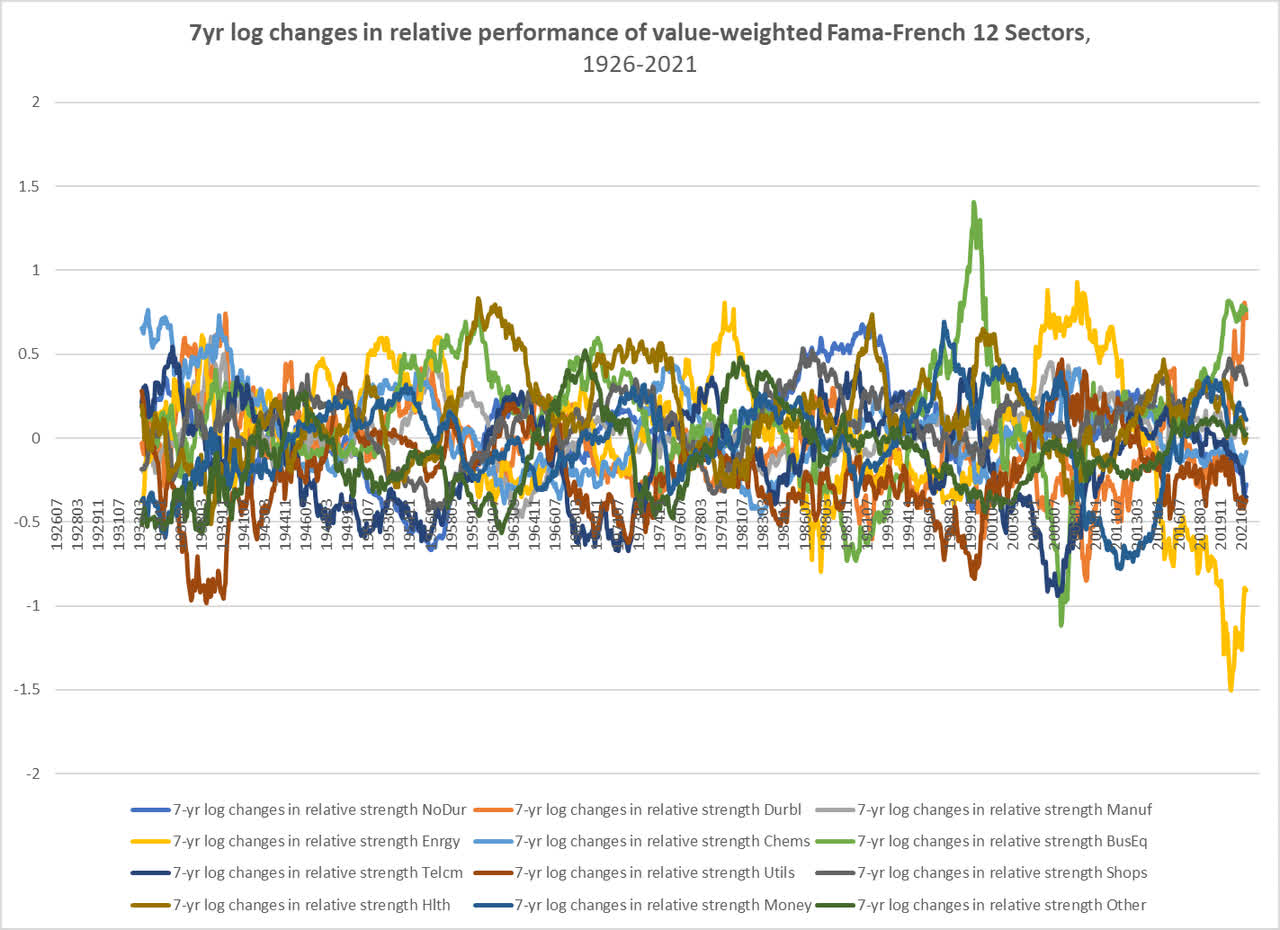

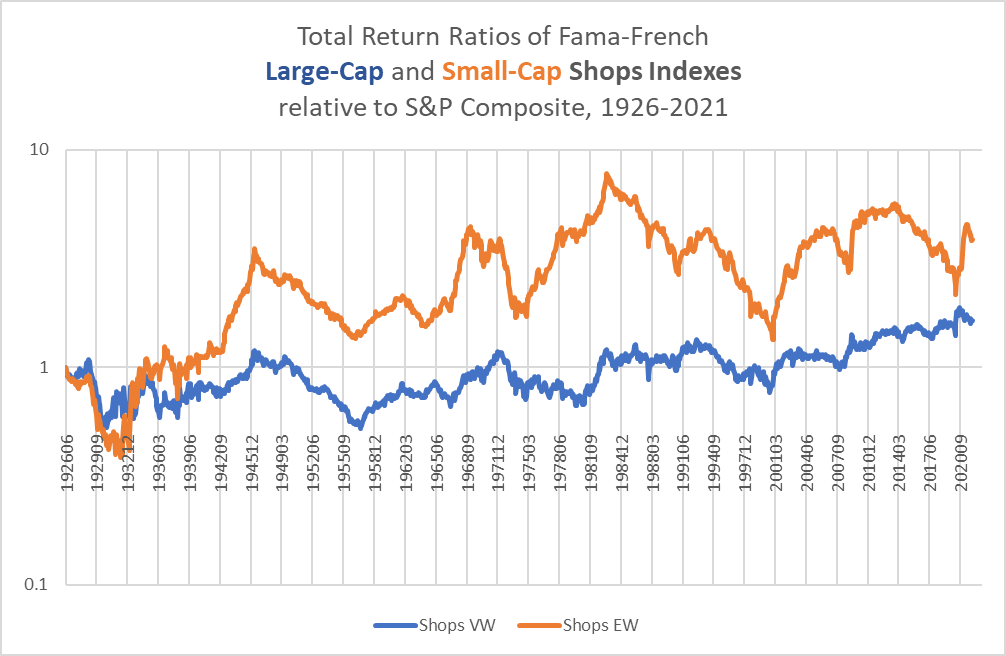

Finally, there is the relationship we mentioned in the introduction. When conditions are suitable for long-term sector rotations (high sectoral dispersions, an alteration in the energy regime, and a cyclical energy shock), then, over the next seven years, “Every valley shall be raised up, every mountain and hill made low”. The worst-performing sectors become the best-performing sectors and vice versa.

It may not be easy to see in the following chart, but it shows that the three top-performing sectors as of the end of 2021 were Business Equipment (green), Consumer Durables (orange), and Shops (dusky purple?) by far.

Chart G. High sectoral dispersion and high-flying XLY performance likely to be bad in the future. (Fama-French)

In other words, two of the top three performing Fama-French sectors are the primary components of the Consumer Discretionary sector. The Durable goods sector is dominated entirely by Tesla.

The extremely high valuation and the broader macro context point to sharply lower returns in the Durable goods sector and the Autos industry for the remainder of the decade.

This talk of sector rotations is a good segue way into the Shops sector.

Shop till you drop

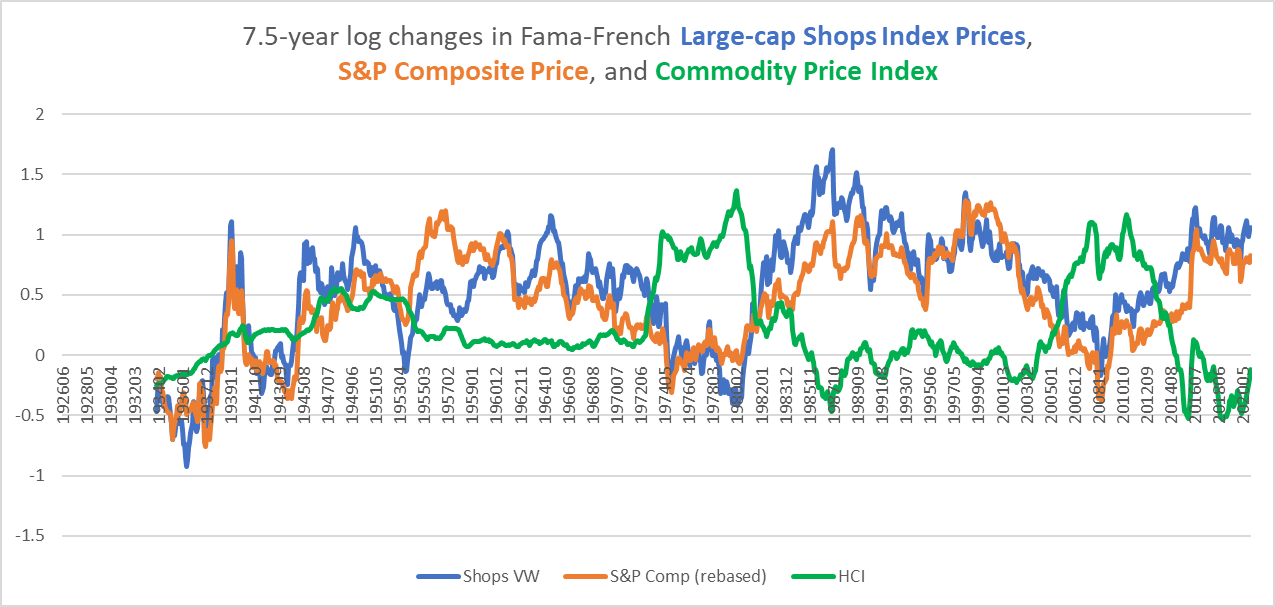

History suggests that Shops will underperform until 2030, per the logic of sector rotations recounted above and in greater detail in previous articles. But, let’s set that aside and see how the Shops sector-again, retail and restaurants-have behaved historically.

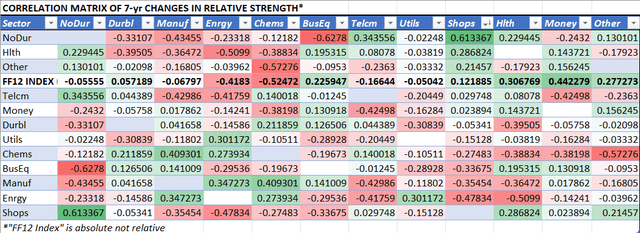

The table below is a correlation matrix showing 7-year relative performances of the Fama-French 12 sectors since 1926.

Table 3. Shops stocks are highly correlated with Nondurables and negatively correlated with Energy. (Own calculations from Fama-French)

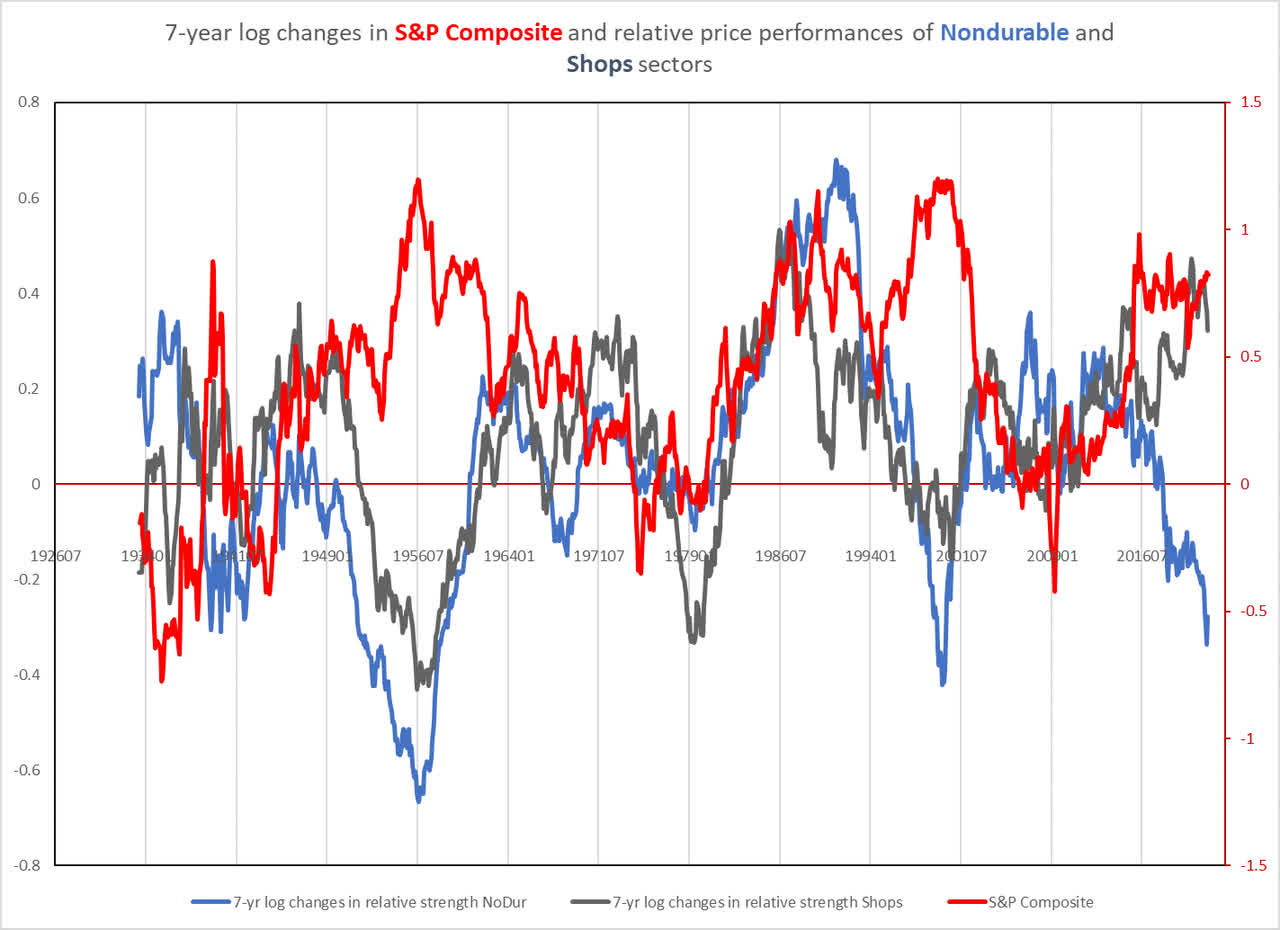

Shops are quite h2ly correlated with Nondurables (a proxy for consumer staples (XLP) and negatively correlated with the relative performance of the Energy sector. Interestingly, as the following chart shows, the last seven years have seen one of the sharpest divergences in the respective relative performances of Shops and Nondurables.

Chart H. Shops and Nondurables are highly correlated but something has broken that correlation over last five years. (Fama-French, Shiller)

I have not yet broken down the Nondurables sector, but a glance at the correlation matrix above suggests that Nondurables tend to do poorly during tech booms. From the Shops end, it is possible that the primary cause for this divergence is the performance of Amazon, but the story is not as one-sided as we found it with respect to Tesla’s place in the auto-universe.

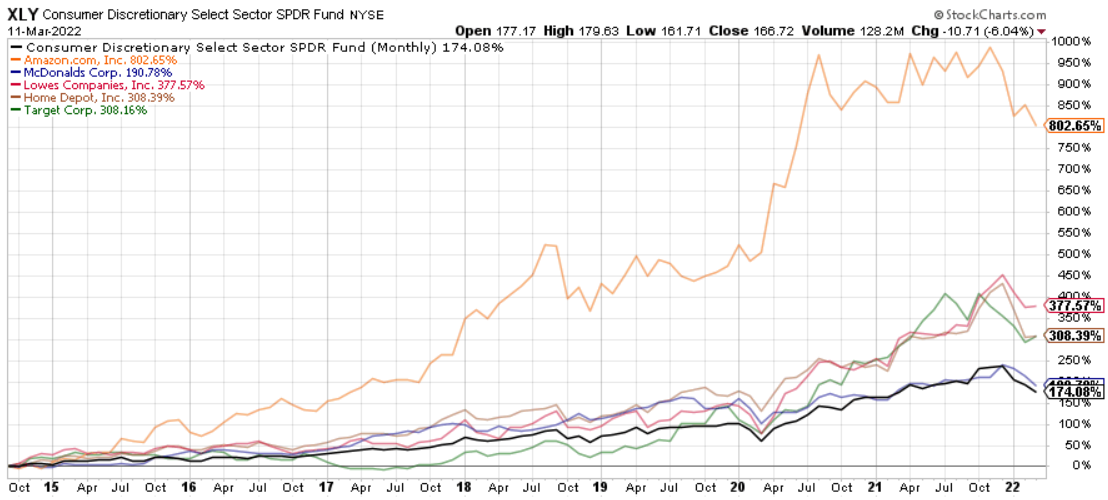

The following chart, for example, shows the top five Shops stocks of the XLY. Four of them are retailers (Amazon, Lowe’s, Home Depot, and Target) and one is a restaurant (McDonald’s).

Chart I. Retailers have been led by Amazon (Stockcharts.com)

Amazon has done consistently well, of course, but all four of those retailers have been net contributors to XLY’s performance, and McDonald’s has been no slouch.

In other words, it seems that at least with Amazon, Shops have caught the tech bug, but we are not presented with the same anomalies found in the auto industry.

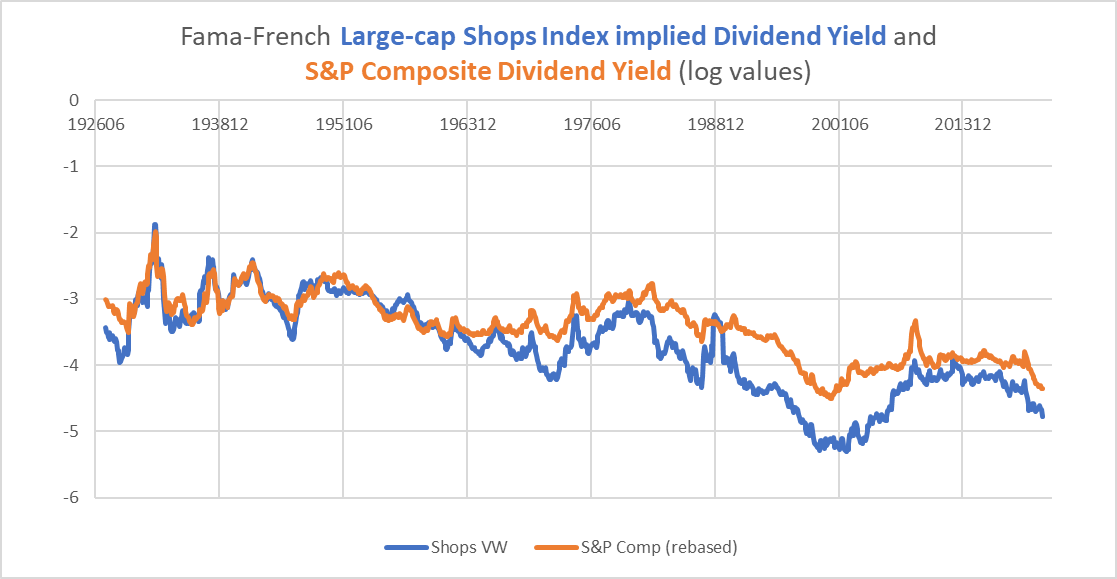

The following chart shows the dividend yield for the Shops sector (calculated by contrasting total and price returns indexes) alongside the S&P Composite’s dividend yield.

Chart J. Shops dividend yield is second lowest trough ever. (Fama-French, Shiller)

Much as we saw with Entertainment stocks in the XLC, the dividend yield began to fall relative to the S&P 500’s yield starting in the mid-1960s, and extreme lows appeared to coincide with peaks in “secular” bull markets for stocks in general.

Generally, long-term performance in Shops stocks tends to track the broader indices.

Chart K. Shops stocks don’t like high commodity inflation or growth shocks. (Fama-French, Shiller, World Bank, Warren & Pearson, St Louis Fed)

They do not like high commodity inflation, but they do especially poorly during dual deflation/growth shocks, as suggested by the following chart illustrating the relative weakness of large-cap Shops stocks during the 1930s.

Chart L. Large-cap stocks underperformed during the Depression. (Fama-French, Shiller)

In the article on XLC and in some other previous articles, I have talked about a class of stocks I call “Baumol stocks”. These are stocks that appear to have benefitted from the process of cost disease, i.e., stocks in the tech and services sectors. These Baumol stocks underperform during bear markets and are especially damaged during deflationary bear markets. The Shops sector appears to be one of them.

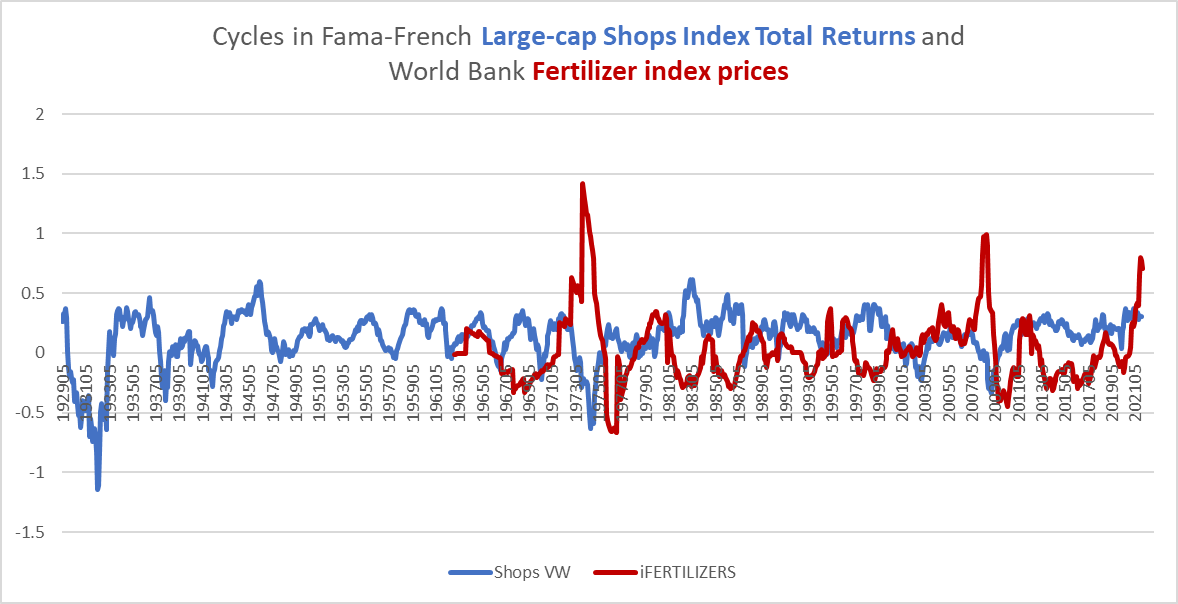

They are also vulnerable to cyclical commodity shocks, with fertilizer and energy prices being among the most negatively correlated.

Chart M. Shops stocks hate fertilizer inflation. (Fama-French, World Bank)

Historically, these shocks appear to have pushed Shops stocks down and continued to exert downward pressure even after having peaked.

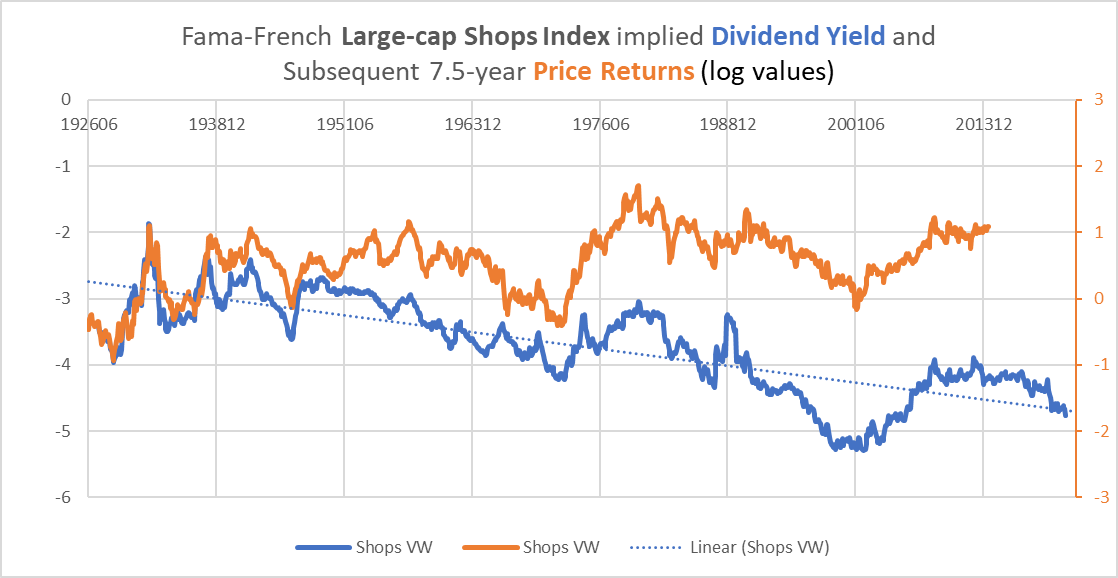

Finally, let’s return to the dividend yield.

Chart N. Shops stocks dividend yield points to lower returns until 2030. (Fama-French)

The detrended dividend yield has a 0.78 correlation with subsequent total returns, but I think the truth lies somewhere between the detrended yield and the actual level of the yield.

Dividend yields have been pushed down by a combination of a structural rise in PE ratios and decline in dividend payout ratios in most stocks. As I argued in “The Death of Irrational Exuberance” (linked to in the text above), that period of structurally rising PEs is likely drawing to a close, so I think it is possible that we have effectively reached something like Peak Valuations in the market.

Therefore, I think returns are likely to be significantly lower than that naively suggested by deviations from a linear trend.

As a commodity shock continues to push cyclical returns down in Shops stocks, this will likely accelerate over the next two years, even as the commodity shock abates through demand destruction and a growth shock. Commodities will likely decline from their currents peaks (see my most recent piece on commodities), but their long-term performance is likely to be stable in contrast to the freefall in most prices in the 2014-2020 period. Flat commodity inflation is likely to be sufficient to suppress returns for the market as a whole and for “Baumol stocks”-tech, consumer discretionary, and communication services-in particular.

Conclusion

In the Consumer Discretionary sector, we have seen technological patterns-these late-bull market booms–“infect” the retail and auto industries in particular, boosting returns and valuations to what are likely unsustainable highs. Amazon and Tesla are the avatars of this process, to mix metaphors. A combination of a reversion to (and likely overshoot of) the historical mean in these industries will likely depress returns throughout the remainder of the decade. At the cyclical level, high commodity inflation has likely already triggered the avalanche.

This does not mean that these stocks will go straight down until 2030. Rather, we are likely to see powerful cyclical bear markets interspersed with powerful cyclical rallies. But, the end result, it seems to me, is likely to be flat to negative long-term returns as in the 1930s and 2000s.

In “The Death of Irrational Exuberance”, as well as in subsequent articles, I have tried to plot out various strategies for dealing with a long-term bear market from establishing a defensive portfolio to trying to trade through the cycle. In my opinion, apart from very opportunistic trades or meticulous stock-picking, there is very little reason to be long the XLY for the next one to three years.

[ad_2]

Source links Google News