HOUSTON — Fixing the damage done by the attack on the Saudi oil processing plant may be the easy part. The hard part will be calming energy markets, where oil prices have jumped faster than at any time in over a decade.

The attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq plant, which accounts for 5 percent of global oil supplies, and a nearby facility took 5.7 million barrels a day of production off line for at least a few days. It also highlighted the vulnerability of the sprawling processing plants, pipelines and refineries of the Persian Gulf.

“The psyche has been altered,” said Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis for Oil Price Information Service. “Now you have the thought, ‘What if the other shoe drops and we have a wider conflict?’”

For years, American and Saudi security analysts have worried about the Abqaiq processing center, which removes sulfur impurities and makes crude oil less volatile so it can be safely exported on tankers. Without the plant, much of the oil that Saudi Arabia produces at its giant Ghawar and Shaybah oil fields would have nowhere to go.

The facility has a heavily guarded perimeter, which was substantially fortified after several cars carrying suicide bombers from Al Qaeda attacked it in 2006. Guards stopped those attackers before they reached the complex’s gates. But the security measures at the site were not sufficient to stop the sophisticated weekend attack that crippled critical components.

While a production shortfall from an attack on one pipeline or refinery can often be offset by others, it is not easy to make up for the loss of the processing capacity of Abqaiq, the largest facility of its kind in the world. The fires were quickly put out, and repairs have begun. But a return to full capacity may take months, energy experts said.

“This changes the oil markets psychologically for a couple of years for sure now that everything is shown to be vulnerable,” said Dragan Vuckovic, president of Mediterranean International, an oil service company that works in Egypt and Iraq. “One drone can hit a refinery or an oil-field installation and that causes fires, destruction and stops all production. It means less oil on the market and higher oil prices.”

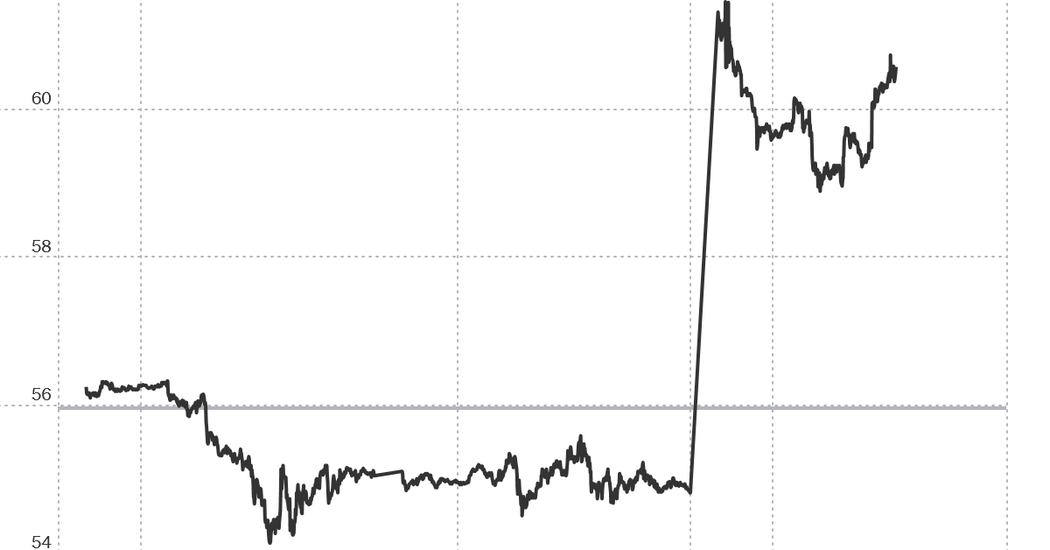

Oil futures shot up 20 percent when trading began in Asia on Monday morning before falling back a little later in the day. It was still the biggest one-day oil price shock since Hurricane Katrina shut down production at Gulf Coast refineries and offshore oil fields in 2005, Mr. Kloza said.

The United States benchmark oil contract settled up $8.05 a barrel, or nearly 15 percent, at $62.90 on Monday. That is still about 7 percent below the price of a year ago. Brent oil, the global benchmark, also rose nearly 15 percent.

Prices might have jumped even more had global oil supplies not been bountiful, analysts said. It also helps that the global economy is slowing, oil production is surging in the United States and many industrialized nations have large strategic oil reserves.

The world has an estimated 90-day supply of oil available, and the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Iraq have spare production capacity. New oil pipelines between West Texas and the Gulf Coast are near completion and will soon increase American exports to countries like South Korea and Japan that depend on Saudi crude. And producers that have been dropping rigs in recent months will likely drill more if prices stay elevated.

Over the weekend, Saudi Arabia tried to quicken the pace of tanker traffic from its ports to cushion the market shock.

Rob Thummel, managing director at Tortoise Advisors, a firm that makes energy investments, predicted a price increase of 10 to 20 percent until there is a complete assessment of the damage at the Saudi plant.

“In the long term, oil prices will likely add a geopolitical risk premium of at least $5 to $10 into the price until the odds of another strike are reduced,” he said.

Mr. Thummel projected that oil prices in the United States would settle between $60 and $70 a barrel, which would lead to a roughly 25-cent increase in the retail price of gasoline.

Americans burn about 400 million gallons of gasoline a day, so a 25-cent increase would cost consumers about $100 million a day. The national average price for regular gasoline on Monday was $2.56 a gallon, 29 cents below a year ago. Experts say the drop in gas prices over the last year has given consumers some extra disposable income — something now likely to disappear.

For many years, analysts believed that higher oil prices always hurt the American economy. But in recent years, that has changed. States like Texas, Louisiana, New Mexico, North Dakota and Colorado benefit when oil prices move up.

Higher prices also help smaller oil companies and oil service companies, which have been laying off workers and struggling to pay debts in recent months. The share prices of several oil and gas company stocks, including Carrizo Oil & Gas, Chesapeake Energy, Apache and Hess, jumped by more than 10 percent on Monday.

Higher oil prices could also reduce the trade deficit now that the United States is a major exporter.

There may also be an upside for steel companies and manufacturers that supply pipes and other equipment to the energy industry. The ethanol industry will also benefit, Mr. Kloza said, because biofuels will become more attractive relative to oil. That should help corn farmers in the Midwest.

That said, higher oil prices could further slow a weakening global economy, especially if the attack on Abqaiq leads to more violence in the Middle East.

“If a full-fledged war between Iran and Saudi Arabia breaks out, there would be no limit to how high prices could go,” said Jay Hatfield, portfolio manager at InfraCap MLP, an exchange-traded fund that invests in oil pipelines.

Even without a war, global supplies could get tighter. Pipelines in the United States remain congested, which will probably reduce daily releases from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve should the Trump administration decide to tap that resource. Countries like Japan and South Korea tend to be reluctant to tap their oil reserves except during full-scale crises.