President Trump on Tuesday confirmed that he is considering “various tax reductions,” including a payroll tax cut, to stimulate the economy as many of the indicators his administration has used to showcase a Trump-fueled economic “boom” have fizzled on the back of the president’s escalating trade fights.

Companies that Mr. Trump has pointed to as signs of economic strength are now warning of weakness. United States Steel, an early champion of Mr. Trump’s metal tariffs and a frequent mention in the president’s Twitter feed, is idling workers and slowing production at a plant in Michigan. Home Depot on Tuesday lowered its sales outlook for the year as it braces for consumer spending to take a hit from Mr. Trump’s Chinese tariffs.

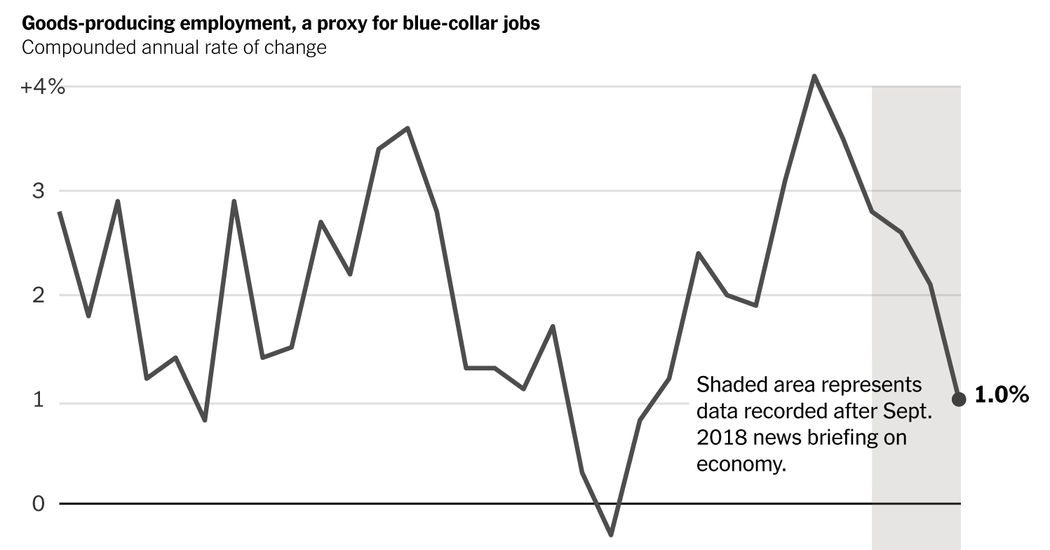

Consumer and small business optimism have fallen, and two in five economists surveyed by the National Association of Business Economists now expect the economy to slip into recession this year or next. Blue-collar job growth has fallen to its lowest level since Mr. Trump took office, and key surveys of manufacturing activity are near recession levels. Economic growth, which Mr. Trump once promised would soar as high as 5 or 6 percent annually, is now running at about a 2 percent annualized pace.

Mr. Trump, speaking to reporters at the White House, continued to portray the economy as “incredible” and played down any chance that the United States could enter into a recession. Any tax cut, he said, would not be done as a defensive move.

“I’ve been thinking about payroll taxes for a long time,” he said. “Whether or not we do it now, it’s not being done because of recession.”

In addition to potentially cutting payroll taxes, which would benefit workers by putting more money in their paychecks, Mr. Trump told reporters that he was thinking about unilaterally reducing capital gains taxes. Such a move would largely benefit wealthy investors by reducing the amount of taxes owed on profitable sales of stocks, bonds and other investments.

The economy is still growing and unemployment remains at a 50-year low. But several of the administration’s favorite economic data points now show unmistakable signs of a slowdown. Business investment has stalled and it slipped backward in the spring.

The indicators suggest that the effects of Mr. Trump’s trade fights with China and Europe and a slowdown in global growth are dragging on the American economy and eroding the short-term boost from the president’s 2017 tax cuts. Economists, including those at the Federal Reserve, say uncertainty from Mr. Trump’s trade policies and the impact of higher tariffs are the biggest threat to the American economy. Mr. Trump is prepared to impose new rounds of tariffs on imports from China in September and December, which will affect a large batch of consumer goods, and he has threatened to impose tariffs on imported automobiles next year.

Mr. Trump suggested on Tuesday that his fight with China would be worth some economic pain — including a brief recession — if it helped reduce America’s $500 billion trade deficit in goods with China.

“Whether it’s good or bad, the short term is irrelevant,” he said. “We have to solve the problem with China because they’re taking out $500 billion a year plus. And that doesn’t include intellectual property theft and other things. And also, national security, so I am doing this whether it’s good or bad for your statement about, ‘Oh, will we fall into a recession for two months?’”

It is unclear when — or if — the economy will tip into recession but much of the economic progress that the White House has cited, including in a series of charts last fall, has already lost steam.

Last September, administration officials walked reporters through a series of charts that they said showed the economy, under Mr. Trump, outperformed what had been its trend in the second term of President Barack Obama.

“I can promise you that economic historians will 100 percent accept the fact that there was an inflection at the election of Donald Trump and that a whole bunch of data items started heading north,” Kevin Hassett, then the chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, told reporters.

Nearly a year after that briefing, almost every data point the administration presented has headed south.

Perhaps the most significant shift has come in capital investment, which Republicans inside and outside the administration promised would skyrocket after Mr. Trump signed a $1.5 trillion tax package that included steep cuts in the corporate tax rate and other incentives for companies to invest immediately. The charts showed nonresidential investment — money pumped into things like plants, property and equipment — surging to 8 percent growth under Mr. Trump.

New versions of those charts, updated by The New York Times to include more recent economic data, show investment growth was already slowing, or was on the cusp, last September. By this spring, it had fallen below the average quarterly growth rate for Mr. Obama’s second term.

That’s also true for the rate at which companies invested in new and updated equipment.

The falloff is evident even when using the administration’s preferred method for calculating growth rates. That method averages growth rates for investment over the previous six quarters, which smooths out temporary spikes in the data to show a more consistent trend line.

The final chart showed investment growth under Mr. Trump running well above forecasts made by the Congressional Budget Office in April 2018, after the tax law went into effect. That boost is no longer the case — and has not been, since last fall.

A similar story has played out in several gauges of manufacturing activity that White House officials highlighted in their briefing. The Institute for Supply Management’s Purchasing Managers’ Index, a closely watched measure of manufacturing health, has fallen to just above recession levels.

Growth in core capital goods orders, a leading indicator of capital spending, has flatlined. And job growth in goods-producing industries, which White House officials used as a proxy for blue-collar jobs, has dropped to just 1 percent.

Other indicators have also weakened since the White House trumpeted them, including the rate at which Americans between the ages of 25 and 54 are working and several measures of optimism among small business owners.

Fed officials have cited the trade war in moving to cut rates, a pattern that could continue with additional cuts this fall.

“When there’s a sharp confrontation between two large economies, you can see effects on business confidence pretty quickly and on financial markets pretty quickly,” Fed Chair Jerome H. Powell said at a news conference earlier this month.

The acting chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Tomas Philipson, said in an email last week that “the U.S. economic outlook remains strong despite slowing global growth.” He stressed that the manufacturing index remained higher than 70 percent of countries in the world, and said that standard economic models would predict the decline in investment growth after an initial spike.

“Part of the current global slowdown,” he said, “is a natural response to the prior period of strong growth.”

Mr. Trump and other advisers blame the slowdown on the Federal Reserve, which they say choked off growth by raising interest rates too fast in 2018. The Fed has since reversed one of its quarter-point rate increases, but Mr. Trump has called for it to cut rates by another percentage point.

“I think that we actually are set for a tremendous surge of growth if the Fed would do its job. That’s a big if, frankly,” Mr. Trump said on Tuesday. “The Fed should be cutting.”

Companies have continued to express concern about economic damage from the president’s trade war and some are beginning to tally up financial pain from higher tariffs and prolonged uncertainty.

Craig Menear, the chairman and chief executive of Home Depot, said in an earnings release that the company was reducing sales guidance in part to account for “potential impacts to the U.S. consumer arising from recently announced tariffs.” Executives at department store J.C. Penney said last week that the company is expecting a financial hit from the next wave of China tariffs, which will tax clothing and other retail products. A Kohl’s executive said the retailer had experienced unspecified damage from the first waves of China tariffs and expected additional pain from the upcoming batches.

Jeanna Smialek contributed reporting.