The list of ailments troubling the eurozone economy was already stark: the highest inflation rate on record, energy insecurity and increasing whispers about a recession. This month, another threat emerged. The weakening euro has raised expectations that it could reach parity with the U.S. dollar.

Europe is facing “a steady stream of bad news,” Valentin Marinov, a currency strategist at Crédit Agricole, said. “The euro is a pressure valve for all these concerns, all these fears.”

The currency, which is shared by 19 countries, hasn’t fallen to or below a one-to-one exchange rate with the dollar in two decades. Back then, in the early 2000s, the low exchange rate undercut confidence in the new currency, which was introduced in 1999 to help bring unity, prosperity and stability to the region. In late 2000, the European Central Bank intervened in currency markets to prop up the fledgling euro.

Today, there are fewer questions about the resilience of the euro, even as it sits near its lowest level in more than five years against the dollar. Instead, the currency’s weakness reflects the darkening outlook of the bloc’s economy.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, the euro has fallen more than 6 percent against the dollar as governments seek to cut Russia from their energy supplies, trade channels are disrupted and inflation is imported into the continent via high energy, commodity and food prices.

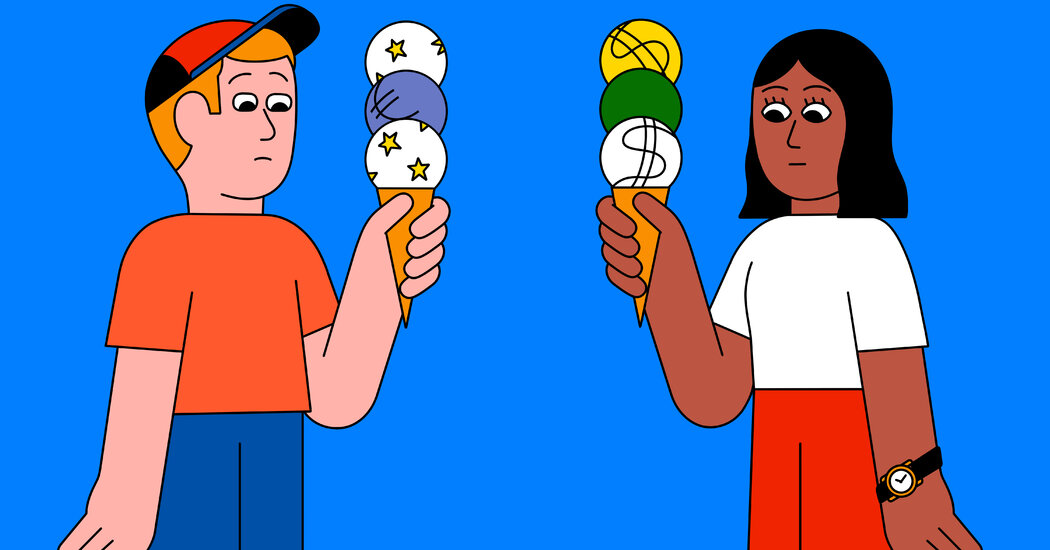

While a weak euro is a blessing for American holidaymakers heading to the continent this summer, it is only adding to the region’s inflationary woes by increasing the cost of imports and undercutting the value of European earnings for American companies.

Many analysts have determined that parity is only a matter of time.

One euro will be worth one dollar by the end of the year and fall even lower early next year, according to analysts at HSBC, one of Europe’s largest banks. “We find it hard to see a silver lining for the single currency at this stage,” they wrote in a note to clients in early May.

Traders are watching to see if the euro will drop below $1.034 against the dollar, the low it reached in January 2017. On May 13 it came close, falling to $1.035.

Below that level, the prospects of the euro reaching parity become “quite material,” according to analysts at the Dutch bank ING. Analysts at the Japanese bank Nomura predict that parity will be reached in the next two months.

For the euro, “the path of least resistance is lower,” analysts at JPMorgan wrote in a note to clients. They expect the currency to reach parity in the third quarter.

Economists at Pantheon Macroeconomics said last month that an embargo on Russian gas would push the euro to parity with the dollar, joining other analysts linking the sinking euro to the efforts to cut oil and gas ties with Russia.

“The outlook for the euro now is very, very tied to the energy security risk,” said Jane Foley, a currency strategist at Rabobank. For traders, the risks intensified after Russia cut off gas sales to Poland and Bulgaria late last month, she added. If Europe’s supplies of gas are shut off either by a self-imposed embargo or by Russia, the region is likely to tip into recession as replacing Russian energy supplies is challenging.

The strength of the U.S. dollar has also dragged the euro close to parity. The dollar has become the haven of choice for investors, outperforming other currencies that have also been considered safe places for money as the risk of stagflation — an unhealthy mix of stagnant economic growth and rapid inflation — stalks the globe. Last week, the Swiss franc weakened to parity with the dollar for the first time in two years, and the Japanese yen is at its lowest level since 2002, bringing an unwanted source of inflation to a country that is used to low or falling prices.

There are plenty of reasons investors are looking for safe places to park their money. Economic growth is slow in China because of shutdowns prompted by the country’s zero-Covid policy. There are recession risks in Europe and growing predictions of a recession in the United States next year. And many so-called emerging markets are being battered by rising food prices, worsening crises in areas including East Africa and the Middle East.

“It’s a pretty grim outlook for the global economy,” Ms. Foley said. It “screams safe haven and it screams the dollar.”

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Global Economy

A far-reaching conflict. Russia’s invasion on Ukraine has had a ripple effect across the globe, adding to the stock market’s woes. The conflict has caused dizzying spikes in gas prices and product shortages, and is pushing Europe to reconsider its reliance on Russian energy sources.

Also in the dollar’s favor is the aggressive action of the Federal Reserve. With inflation in the United States hovering around its highest rate in four decades, the central bank has ramped up its tightening of monetary policy with successive interest rate increases, and many more are predicted. Traders are betting that U.S. interest rates will climb another 2 percentage points by early next year to 3 percent, the highest level since 2007.

In comparison, the European Central Bank has only just begun to send strong signals that it will begin to raise rates, possibly as soon as July. It would be the first increase in more than a decade. But even when policymakers begin, it will probably take more than one policy meeting to get one of the key interest rates above zero. The deposit rate, which is what banks receive for depositing money with the central bank overnight, is minus 0.5 percent. The question being debated by analysts now is how far above zero the bank could get before it has to stop raising interest rates because the economy is too fragile to support them.

In financial markets, the “concern now is that the E.C.B. will be too late to stop a slip towards parity,” Mr. Marinov said.

The central bank has some options — it could raise rates at its next policy meeting in June to surprise the market and prevent the euro from weakening significantly further, or it could embark on a program of raising rates much higher than expected, Mr. Marinov added.

The bank’s policymakers are keenly watching the exchange rate. On Monday, François Villeroy de Galhau, the governor of the French central bank and a member of the governing council of the European Central Bank, said officials were carefully monitoring the exchange rate because it is a “significant” cause of inflation. “A euro that is too weak would go against our price stability objective,” he said.

The euro’s slide could also pose a challenge for American businesses operating in Europe. Last month, Mastercard said that it expected the strength of the dollar relative to the euro to shave off some potential in the company’s growth this year. Johnson & Johnson said the “unfavorable” currency impact on sales would be $2.5 billion for the year.

But the euro’s drop to parity and below isn’t assured. The currency pulled away from its lows this week after a member of the European Central Bank’s governing council suggested that the bank could raise rates in bigger jumps than the expected quarter-basis-point move. On Friday, the euro was trading at $1.058.

Ironically, the euro could resist reaching and falling below parity because that level would be deemed unjustly low. According to Mr. Marinov, parity would mean the euro was undervalued and oversold.

“The deeper we go into that territory, essentially the less convincing chasing the euro lower will become,” he said.