‘Potentially huge stagflationary shock for the world economy’

Article content

Jan Ozubko, a Canadian of Polish and Ukrainian descent, runs Buildome Contracting Ltd. in the Greater Toronto Area and has dreamed of using some of the profits he’s earned during the city’s housing boom over the past decade to build houses in Ukraine.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

The new Cold War between Russia and the United States and its Western allies has effectively forced Ozubko to put those dreams on hold since 2014, when Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Crimea, and then annexed it. The West responded with sanctions, and suspended Russia’s membership in the G8 group of economic powers. The situation has been tense ever since, impeding efforts to strengthen Canada’s economic ties with the country.

“It’s very hard to predict what’s going to happen in the next few years,” Ozubko, 64, said in an interview late last week amid reports that Russia was on the verge of invading Ukraine again. “That’s why, all the time, I’ve postponed my plans.”

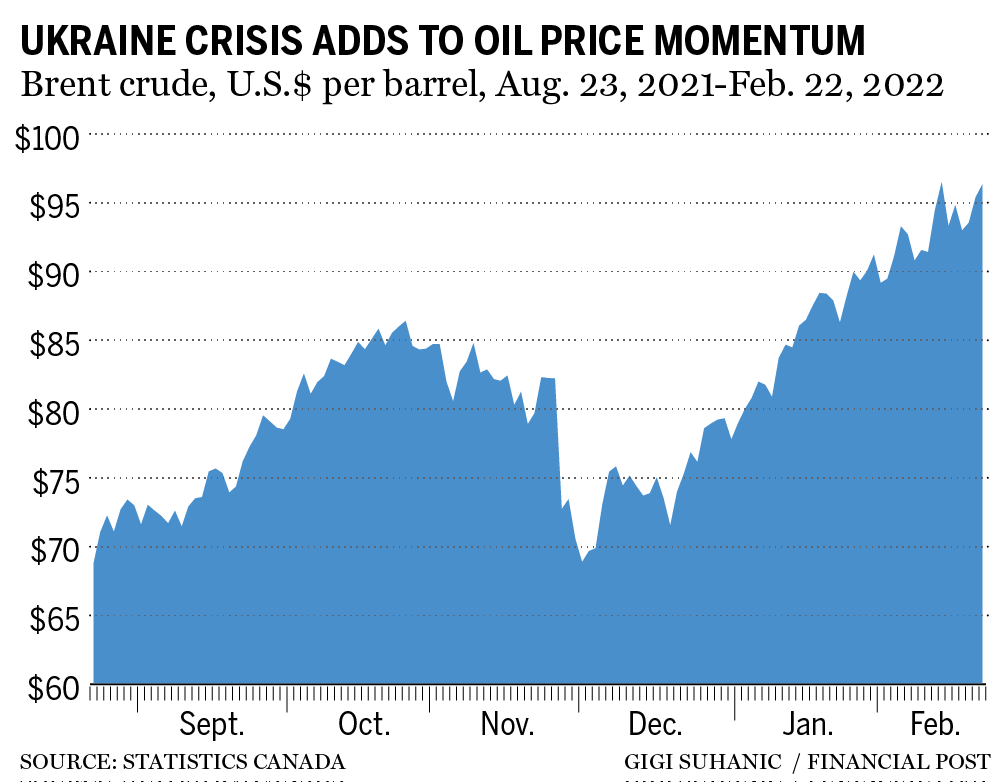

Something akin to an invasion happened on Feb. 21 when Putin sent “peacekeepers” into the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine, where Russian-backed separatist forces have been fighting the Ukraine government in recent years. Global energy prices surged as Western nations, including Canada, promised sanctions in response to Putin’s provocation. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz suspended the approval process for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline that would allow Russia to increase exports of natural gas to the European Union.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

The United Kingdom announced sanctions on five Russian banks and three of the country’s oligarchs, in what Prime Minster Boris Johnson described as the “first tranche” of measures. The EU and United States enacted similar measures. U.S. President Joe Biden announced sanctions that target Russia’s sovereign debt, essentially cutting its government off from Western financing. “It can no longer raise money from the West and cannot trade in its new debt on our markets or European markets either,” Biden said.

Meanwhile, Russia’s parliament voted unanimously to recognize the breakaway states of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said late in the afternoon on Feb. 22 that Canada had banned all financial dealings with Donetsk and Luhansk; applied sanctions on Russian parliamentarians who voted to recognize the breakaway regions and two state-backed banks; and banned Canadians from buying Russia’s sovereign debt.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

Trudeau also said he would deploy 460 members of the Canadian military to support NATO’s Operation Reassurance. “Canada and our allies will defend democracy,” Trudeau said at a press conference. “We are taking these actions today to stand against authoritarianism.”

The heating up of tensions between Russia and NATO put markets on edge. European stocks markets initially fell, then clawed back those losses, perhaps because investors were betting that Putin would stop his advance at Donetsk and Luhansk.

European gas prices surged 10 per cent, and the prices for other commodities such as traders worried about supply disruptions of goods ranging from aluminum, to oil, to wheat. Analyst David Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research & Associates Inc. reminded his clients that while Russia is known for its oil and gas reserves, it and Ukraine account for about 20 per cent of global corn exports and 25 per cent of the wheat supply.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

“This is clearly a potentially huge stagflationary shock for the world economy at a time when pandemic-induced bottleneck pressures were just showing signs of a thaw,” Rosbenberg wrote in his daily report to his clients.

Trade between Canada and Ukraine has been relatively duty free since 2017, when a free-trade agreement took effect, but the pact appears to have done little to offset the political risk that comes with doing business in Russia’s neighbourhood.

The value of Canadian merchandise exports dropped 18 per cent the year after the trade agreement took effect, and then fell again in 2019. Goods exports last year were worth $220 million, about the same as 2018. There is a little more life in imports from Ukraine, which rose to $226 million in 2021, the most since 2005, according to customs data compiled by Statistics Canada.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

Uncertainty “is causing problems for bringing in new investors and doing business,” Zenon Potoczny, the head of the Canada-Ukraine Chamber of Commerce, told the Financial Post’s Larysa Harapyn on Feb. 18. “It’s instability in the country,” he added, citing Russian cyber-attacks on the banking system as an example. “It’s very difficult. Investors are watching, especially with all the Western countries saying, ‘Don’t travel to Ukraine.’”

-

Fears of Ukraine war shake stocks and send oil soaring

-

Germany freezes Nord Stream 2 gas project as Ukraine crisis deepens

-

Companies exposed to Russia brace for new sanctions

Matt Simpson, chief executive of Black Iron Inc., a Toronto-headquartered explorer that is trying to build an iron ore mine in central Ukraine, said the buildup of Russian forces at the eastern border in recent weeks has delayed and damaged his company.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

International consultants have stopped travelling there, and his negotiations with Ukraine to purchase a key piece of land have stalled. Plus, his company’s stock price has declined 18 per cent since the start of the month.

“It has unfortunately hurt our share price, but that’s short term,” said Simpson, a former executive at Iron Ore Company of Canada, a Rio Tinto Ltd. subsidiary. “Once cooler heads prevail, it should rebound.”

It’s not the first time he’s been through this: He was also working on developing the mine in 2014 when Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed the Crimean Peninsula.

“That caused us to put the project on pause because we weren’t sure what was going to happen,” said Simpson.

Now, even though his project is west of the river that divides the country, and Russian forces are gathering on the eastern border, it is threatening his project again, Simpson said, as he works on a feasibility study, environmental study and raising the US$500 million in capital necessary to build it.

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

“It has been hard getting international consultants into Ukraine for obvious reasons, with people being concerned about their safety,” said Simpson, “for that reason we’re trying to use as many local consultants as possible.”

The only silver lining, he said, is that if the situation resolves quickly, Ukraine’s government could be eager to see his project move forward so it can point to a “success story” that shows its economy is still functional.

Indeed, Potoczny said the situation, while tense, wasn’t as bad as it looked. “There is no panic in Ukraine,” he said. “We talk to our friends and our office in Ukraine. Yes, everyone is worried. Everybody is waiting to see what is going to happen, but there is no panic, no rush on taking money out. There is no rush of businesspeople running away.”

But it seems unlikely there will be a rush of business people running in, either. Ozubko said he sees the ebb and flow of Russian invasion into Ukraine as too risky to commit money and eventually retire in his father’s home country, though he regularly visits.

“I’m really worried right now,” he said.

Additional reporting by Gabriel Friedman

• Email: bbharti@postmedia.com | Twitter: biancabharti

Advertisement

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.